1. Цели и задачи дисциплины (модуля)

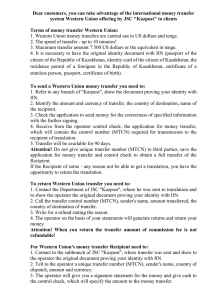

advertisement

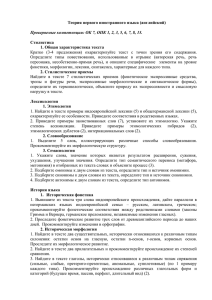

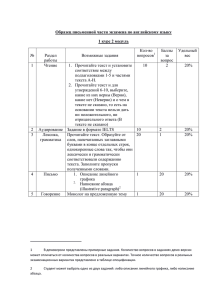

Одобрена кафедрой перевода и теоретической лингвистики Протокол № ___ от «___»_______2011г. ПРОГРАММА ДИСЦИПЛИНЫ (МОДУЛЯ) Аннотирование и реферирование по направлению подготовки 035700.62 «Лингвистика», профиль «Теория и методика преподавания иностранных языков и культур» ФГОС ВПО утвержден приказом МОиН РФ от «20» мая 2010г. № 541 Общий объем курса по учебному плану 3 (zet) 108 (часа) Квалификация (степень) выпускника - бакалавр Нормативный срок освоения программы – 4 года Форма обучения - очная Зав. кафедрой перевода и теоретической «___»_____2011г. _________ (подпись) лингвистики, к.ф.н. Игнатьева Разработчик ст. преподаватель кафедры перевода и теоретической лингвистики Артамонова Алина Альбертовна «___»_____2011г. _________ (подпись) М. Э. 1. Цели и задачи дисциплины (модуля): Основные цели: сформировать умения и навыки чтения литературы любого жанра на языке оригинала с целью извлечения нужной информации для использования в будущей профессиональной деятельности; способствовать развитию переводческой компетенции обучаемых, поскольку знание языковых норм, владение техникой перевода и умелое пользование ими в сфере профессиональной деятельности – одно из важных условий повышения эффективности деятельности будущих специалистов; приобретение навыков полного, реферативного и аннотационного перевода. Задачи дисциплины: - анализировать различные элементы профориентированного текста; - выделять лексические и грамматические трудности перевод; - познакомить студентов с теоретическими основами и методикой аннотирования и реферирования текстов; - научить применению умений и навыков аннотирования и реферирования на практике в комплексе с другими видами переводческой деятельности; - повысить общую культуру чтения литературы разных жанров на родном и иностранном языках. - использовать известные приемы и пути решения переводческих задач. 2. Место дисциплины (модуля) в структуре ООП: дисциплины по выбору - Язык делового общения Б3.В.ОД.12 - Практикум по культуре речевого общения (1-ый ин. яз.) Б3.Б.6 Аннотирование и реферирование Б3.В.ДВ.1.1 - Русский язык и культура речи Б1.Б.3 - Практический курс 1-го иностранного языка Б3.Б.2 3. Требования к результатам освоения дисциплины (модуля): Выпускник должен обладать следующими компетенциями: а) общекультурными (ОК): обладает навыками социокультурной и межкультурной коммуникации, обеспечивающими адекватность социальных и профессиональных контактов (ОК-3); владеет культурой мышления, способностью к анализу, обобщению информации, постановке целей и выбору путей их достижения, владеет культурой устной и письменной речи (ОК-7); умеет применять методы и средства познания, обучения и самоконтроля для своего интеллектуального развития, повышения культурного уровня, профессиональной компетенции, сохранения своего здоровья, нравственного и физического самосовершенствования (ОК-8); стремится к постоянному саморазвитию, повышению своей квалификации и мастерства; может критически оценить свои достоинства и недостатки, наметить пути и выбрать средства саморазвития (ОК-11); понимает социальную значимость своей будущей профессии, обладает высокой мотивацией к выполнению профессиональной деятельности (ОК-12); б) профессиональными (ПК): 2 владеет основными способами выражения семантической, коммуникативной и структурной преемственности между частями высказывания - композиционными элементами текста (введение, основная часть, заключение), сверхфразовыми единствами, предложениями (ПК4); умеет свободно выражать свои мысли, адекватно используя разнообразные языковые средства с целью выделения релевантной информации (ПК-5); владеет методикой предпереводческого анализа текста, способствующей точному восприятию исходного высказывания (ПК-9); владеет методикой подготовки к выполнению перевода, включая поиск информации в справочной, специальной литературе и компьютерных сетях (ПК-10); знает основные способы достижения эквивалентности в переводе и умеет применять основные приемы перевода (ПК-11); умеет работать с электронными словарями и другими электронными ресурсами для решения лингвистических задач (ПК-28); ориентируется на рынке труда и занятости в части, касающейся своей профессиональной деятельности (обладает системой навыков экзистенциальной компетенции - изучение рынка труда, составление резюме, проведение собеседования и переговоров с потенциальным работодателем) (ПК-43). В результате изучения дисциплины студент должен: Знать: - приемы использования опоры на внешнюю и внутреннюю структуру текста, - алгоритмы аннотирования, реферирования и других видов операций по свертыванию текста, - особенности научно-технического текста, - знать композиционно-смысловую структуру аннотаций и рефератов, - внешнюю и внутреннюю структуре текста. Уметь: - пользоваться всеми рабочими источниками информации, - работать с заголовком текста, - применять практические умения, связанные с распознаванием текстовых структур, - пользоваться алгоритмами аннотирования и реферирования. Владеть: - способностью осуществлять предпереводческий анализ письменного и устного текста, способствующий точному восприятию исходного высказывания; - совокупностью умений и навыков, определяемых данной программой и позволяющих переводчику успешно решать свои профессиональные задачи; - способностью осуществлять реферирование и аннотирование письменных текстов. 4. Общий объем дисциплины Общая трудоемкость дисциплины составляет 3 (ZET) 108 (академ. часа) из них отмечены* темы активных/интерактивных аудиторных занятий согласно ФГОС Распределение часов курса «Аннотирование и реферирование» по разделам, темам и видам работ Наименование тем/разделов, коды компетенций подготовки бакалавра, приобретаемых в соответствующих темах Аудиторные занятия (часов) СРС (часов) (Текущий контроль по темам) ZET Всего Лек Практ. КСР Всего Реф. Эссе Др. формы контроля Раздел 1. Понятие текст Тема 1. Внешняя структура текста ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-4, ПК-5, ПК-9 2* 2* 1 6 3 Тема 2. Внутренняя структура текста 2* ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-4, ПК-5, ПК-9 Тема 3. Приемы использования опоры на внешнюю и внутреннюю структуру текста 2* 2 4* 2* 4* 1 6 1 6 1 6 ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-4, ПК-5, ПК-9 Тема 4. Семантическое свертывание текста ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-4, ПК-5, ПК-9 Раздел 2. Научно-технический текст и его лингвистические свойства Тема 1. Основные виды перевода 2 2* 4 10 Тема 2. Полный письменный перевод ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-5, ПК-9, ПК-10, ПК-11, ПК-43 ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-10, ПК-11, ПК-28, ПК-43 Тема 3. Сокращенные виды перевода ОК-3, ОК-7, ОК-8, ОК-11, ОК-12; ПК-10, ПК-11, ПК-28, ПК-43 3 6* 2 10 3 6* 2 10 Не предусмотрено Курсовая работа Контроль (экзамен/зачет/зачет с оценкой) ВСЕГО зачет 3 54 16 28 10 54 0 0 54 5. Содержание дисциплины (модуля) 5.1. Содержание разделов дисциплины № п/п 1. 2. Наименование раздела, темы дисциплины Содержание раздела Раздел 1. Понятие текст Внешняя структура текста Типология текстов: определение понятия "текст"; формы выражения мысли в тексте; особенности научнотехнического и художественного текста. Межфразовые связи. Лексико-тематическая сетка и логическая основа текста: типы межфразовых связей; логическое развитие мысли в тексте; лексическая тематическая основа текста; работа с заголовком. Сегментация текста: типы сверхфразовых единств; субтекст и его разновидности. Внутренняя структура текста Функциональный подход к тексту. Тема и рема. Имплицитность и подтекст: импликация как грамматическое явление; подтекст и способы его формирования. Семантическое свертывание текста: проблема "ядерного текста"; избыточность. 4 Приемы использования опоры на внешнюю и внутреннюю структуру текста Чтение, аннотирование и реферирование с целью извлечения и переработки информации. Практические умения, связанные с распознаванием текстовых структур: овладение типологией текстов; межфразовые связи; понимание логического развития мысли в тексте; работа с заголовками и лексикотематической основой. Индуктивный подход к работе с текстом: принцип перехода от внешней (наблюдаемой) текстовой структуры к внутренней (глубинной) структуре; коммуникативный блок; методика извлечения имплицитного смысла; выявление подтекста в художественном повествовании. Принцип дедуктивного подхода к тексту: приемы визуального моделирования смысловой структуры целого текста; формулирование ядерного высказывания: тема текста, рема текста. Семантическое свертывание Смысловое свертывание при реферировании текста: текста обобщение и абстракция; абстрагированное выражение идеи произведения; интерпретация операций по свертыванию текста в коммуникативном плане. Алгоритмы реферирования и аннотирования: реферат; аннотация; алгоритм составления реферата и аннотации. Другие виды операций по свертыванию текста: пересказ текста; адаптация текста; реферативный перевод. Раздел 2. Научно-технический текст и его лингвистические свойства Основные виды перевода Основные виды перевода. Важные этапы письменного перевода. Особенности перевода научно-технической литературы. Понятие - термин. Многофункциональные слова. Лексические и грамматические трансформации при переводе. Изменение структуры предложения при переводе. Чтение и полный перевод текста по специальности. Полный письменный Научно-технический текст и его лингвистические свойства перевод (тема текста, структура текста, межфразовые связи, логическая структура абзаца). Формы обмена специальной научно технической информацией. Сокращенные виды перевода Аннотирование и его сущность. Виды аннотаций. Реферативный перевод и его сущность. Виды рефератов. Виды устного сокращенного перевода. Полный и сокращенный перевод патентов. Другие виды свертывания текста. 3. 4 1. 2. 3. 5.2. Активные и интерактивные формы обучения № п/п № раздела (темы) 1. Раздел 1. Тема 1. Форма и её описание Трудо ёмкость (часов) Интерактивная форма. Презентация в программе 3 PowerPoint: Типология текстов Диспут: Определение понятия "текст". 5 2. Раздел 1. Тема 2. 3. Раздел 1. Тема 3. 4. Раздел 1. Тема 4. 5. Раздел 2. Тема 1. 6. Раздел 2. Тема 2. 7. Раздел 2. Тема 3 Различные взгляды на тему. Интерактивная форма. Презентация в программе PowerPoint: Тема и рема Диспут: Функциональный подход к тексту. Диспут: Работа с заголовками: определяющие принципы. Интерактивная форма. Презентация в программе PowerPoint: Алгоритмы реферирования и аннотирования. Диспут: Интерпретация операций по свертыванию текста в коммуникативном плане. Интерактивная форма. Презентация в программе PowerPoint: особенности научно-технического и художественного текста. Обсуждение в группе. «Мозговой штурм» типичных примеров переводческих трудностей может проходить в группе или группах студентов как с участием, так и без участия преподавателя. Круглый стол: Аннотационный и реферативный перевод в специальных сферах. Востребован ли данный вид перевода в Казани. Диспут: Перевод патентов: сегодня и вчера. 3 2 3 2 4 4 5.3 Разделы дисциплины и междисциплинарные связи с обеспечиваемыми (последующими) дисциплинами № п/п 1. 2. Наименование обеспечиваемых (последующих) дисциплин Язык делового общения Практикум по культуре речевого общения (1-ый ин. яз.) Практикум по культуре речевого общения (1-ый ин. яз.) № № разделов и тем данной дисциплины, необходимых для изучения обеспечиваемых (последующих) дисциплин 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 2.1 2.2 2.3 + + + + + + 6. Лабораторный практикум Не предусмотрено 7. Практические занятия. Примеры заданий для работы студентов на занятиях Методические рекомендации 1. Пользуясь источниками информации, найдите в приводимых ниже отрывках эквиваленты подчеркнутых слов и сочетаний. Учитывайте контекст отрывка. Помните, что многие термины состоят из нескольких слов, причем это может быть свободное сочетание, смысл которого выводится из смысла компонентов и несвободное словосочетание, смысл которого не является суммой значений компонентов. В первом случае, если словарь не дает эквивалента сразу для всего сочетания, нужно искать эквиваленты частей сочетания, а во втором – обязательно найти эквивалент всего выражения. Если из контекста ясно, что данное выражение – технический или научный термин, то искать его в общем фразеологическом словаре обычно бесполезно. 6 Light dimmers for electric lamps Simple dimmers for electric lamps that fit right into a standard lamp socket and give stepless control from full bright to dim will standard home equipment in the near future. The dimmers would use a built-in potentiometer with a switch in place of the simple on-off switch now used. Miniature solidstate electronic circuitry would be built into the socket. Is there such a thing as a straight river? Almost anyone can think of a river that is more or less straight for a certain distance, but it is unlikely that the straight portion is either very straight or very long. In fact, it is almost certain that the distance any river is straight does not exceed 10 times its width at that point. The sinuosity of river channels is clearly apparent in maps and aerial photographs, where the successive curves of a river ten appear to have a certain regularity. In many instances the repeating pattern of curves is so pronounced that it is the most distinctive characteristic of the river. Such curves are called meanders, after a winding stream in Turkey known in ancient reek times as the Maiandros and today as the Menderes. Vaccine for German Measles Success in preliminary tests of a vaccine made from an attenuated live strain of the rubella virus, the causative agent, of hat was once deemed a trivial childhood disease, was announced at the April meeting of the American Pediatric Society in Atlantic City by Paul D. Parkman and Harry M. Meyer. The virulent effect of rubella or "German measles", on unborn children was not recognized until 1941, when the Australian ophthalmologist Norman Gregg was able to relate cases of cataract, in children to their mothers' history of rubella early in pregnancy. 2. Сделайте полный письменный перевод приведенного ниже текста. Energy from the sun Our period of history is sometimes called the atomic age, but scientists and engineers continue to investigate other new sources of energy. During the past few years, there has been much interest in the possibility of converting the energy of the sun into useful power. Radiation, the fuel for solar energy, is the radiation which the sun transmits to the earth through some 92,500,000 miles of virtually empty space. The distribution of radiation intensity throughout the solar spectrum tells us that the sun's surface temperature is about 10,000°F. The temperature of the sun's interior is estimated to be 30,000,000°F. Solar energy is measured in terms of the heat produced when the radiation falling on a surface is completely absorbed. The rate at which solar energy reaches the earth's atmosphere is known as the solar constant. The radiant energy which reaches the outer fringes of our atmosphere is materially reduced by scattering and absorption before it reaches the earth's surface. On a clear day, at sea level, the direct radiation may range from 250 to 320 BtU/ft2hr. The 30 to 40 per cent which is scattered by dust and absorbed by air molecules, water vapor, etc., is not entirely lost, because about half of it reaches the earth as diffused radiation. The total usable solar energy is the sum of these two components. A concentrating collector, such as a solar furnace, can use only the direct radiation which travels in straight lines and can be focussed. A flat plate collector can use both the direct and the diffused radiation. The total amount of radiation which reaches a collector on the earth's surface depends upon the number of hours of sunshine per day, and the thickness and nature of the atmospheric path through which the sun's rays must travel. Most of the inhabited areas of the world receive plenty of solar energy to meet all of man's requirements. The problem which the engineer must solve is how to use this abundant supply of free income energy at a total cost which is within our ability to pay. The large-scale industrial use of the sun's power becomes a reality. As an example, a solar power station is reported to come soon into use on the sunny Ararat Plain in Armenia. It will be one of the first solar power stations in the world with a capacity of 1,200 kw. The station is supposed to generate annually 2,5 million kw of electric power and 20,000 tons of steam. 7 The Ararat Plain has been chosen for the first station because of its being one of the places with the greatest amount of sunshine: it is recorded to get 2,600 hours of sunshine a year. Each square yard of surface gets well over 2,250 million calories of heat a year. We expect the solar station to look very different to the usual power plant - no smoky chimneys, no giant dams. The unit will consist of an enormous circle with trees around it to cut down the amount of dust. In the centre there will be a 130 foot tower with a high pressure boiler installed at the top of it. Around the tower 23 concentric circular railway tracks are being built. Along them trains, automatically following the movement of the sun, will pull 1293 large mirrors mounted on special cars. The mirrors will always be directed towards the sun by means of automatic relays thus reflecting the beams on the flat surface of the boiler. Other automatic devices, synchronised with the trains, will adjust the angle of the boiler so that all these beams reflected from the mirrors fall on it perpendicular. The sun's rays will heat the water in the boiler, from which steam at a pressure of 30—35 atmospheres will be piped off to the 1,200 kw steam turbine the same way as ordinary boilers operating with ordinary fuel. The station will be able to operate only when the sun shines. The sun's rays falling upon photoelectric cells, the whole apparatus will automatically go into operation. The power from the station will be used for operating irrigation pumps on the local farms, and the waste steam from the turbines can be used for providing ice. Hot water from the station stored in underground reservoirs will serve the purpose of heating hot-houses and private homes. 8. Примерная тематика курсовых проектов (работ): Не предусмотрено 9. Учебно-методическое и информационное обеспечение дисциплины: Основная литература: 1. Володарская Е.Б. Английский язык. Методология написания рефератов // Учеб. пособие // Е.Б. Володарская, М.М. Степанова. - СПб.: Изд-во Политехн. ун-та, 2009 2. Латышев Л.К. Технология перевода: уч. пос. для студ. вузов. – М.: Академия, 2008. – 320 с. 3. Пичкова Л.С., Бочкова Ю. Л., Маслина И. Н., Пантюхина Л. В. Экономический английский: перевод, реферирование и аннотирование. Теория и практика. – М.: МГИМО, 2008. – 434 с. 4. Слепович В. С. Настольная книга переводчика с русского языка на английский = Russian – English Translation Handbook. – Мн.: ТетраСистемс, 2008. – 304 с. 5. Тексты из научно-технической и научно-популярной литературы, журналы “Time”, “Economist”, Интернет сайты. 6. Журнал «Мир перевода». Дополнительная литература: 1. Беспалова Н.П., Котлярова К.Н., Лазарева Н.Г., Шейдеман Г.И. Перевод и реферирование общественно-политических текстов: учеб. пособие. - М.: Дрофа, 2006. - 127 с. 2. Васильева М.А., Закгейм Е.И. Обучение реферированию научной литературы - М.: Высшая школа, 1986 3. Вейзе А.А. Чтение, реферирование и аннотирование иностранного текста: Учеб. Пособие. – М.: Высшая школа, 1995. – 127 с. 4. Гарбовский Н.К. Теория перевода: Учебник. – М.: Изд-во Моск. ун-та, 2004. – 544 с. 5. Григоров В.Б. Как работать с научной статьей. Пособие по английскому языку: Учеб. Пособие. – М.: Высшая школа, 2001 6. Климзо Б. Н. Ремесло технического переводчика. Об английском языке, переводе и переводчиках научно-технической литературы. - М.: Р. Валент, 2006. – 508 с. 7. Мифтахова Н.Х. Пособие по английскому языку для III-IV курсов химико-технологических вузов. – М.: Высшая школа, 1991 8. Рубцова М. Г. Чтение и перевод английской научной и технической литературы: лексикограмматический справочник. – М.: АСТ: Астрель, 2006. – 382, [2] с. 8 9. Чебурашкин Н.Д. Технический перевод в школе / Н.Д. Чебурашкин.-М.: Просвещение,1993.-255 с 10. Чужакин А. П. Последовательный перевод: практика+теория. Синхрон. Для V курса переводческих факультетов. - М.: Р. Валент, 2005. – 272 с. Базы данных, информационно-справочные и поисковые системы: 1. www.translators-union.ru 2. www.russian-translators.ru 3. www.trworkshop.net 4. www.bokorlang.com/journal 5. www.multitran.ru 6. www.google.com 10. Материально-техническое обеспечение дисциплины: Книжный фонд библиотеки, доступ к глобальной сети Интернет, различные технические средства обучения. 11. Методические рекомендации по организации изучения дисциплины: Семинарские (практические) занятия — одна из важных форм аудиторных занятий со студентами, обеспечивающая наиболее активное участие их в учебном процессе и требующая от них углублённой самостоятельной работы. В планах для подготовки студентов к занятию сформулированы вопросы, определены номера задач или упражнения, которые необходимо решить при домашней подготовке или обсудить в ходе аудиторных групповых занятий, указаны контрольные вопросы или тесты для самопроверки. При домашней подготовке к занятиям по каждой теме студенты должны проработать конспекты лекций, литературные источники, выбрать дополнительную литературу по своему усмотрению, подготовить ответы на вопросы, практические задания и т.д. Сформулированные вопросы и задачи в планах занятий по теме коллективно обсуждаются. По мере необходимости в ходе занятия преподаватель может задавать другие вопросы. Самостоятельная работа студентов, предусмотренная учебным планом, должна соответствовать более глубокому усвоению изучаемого материала, формировать навыки исследовательской работы и ориентировать их на умение применять теоретические знания на практике. В процессе этой деятельности решаются следующие задачи: - научить работать с учебной литературой; - формировать у них соответствующие знания, умения и навыки - стимулировать профессиональный рост студентов, воспитывать творческую активность и инициативу. Самостоятельная работа студентов предполагает: - подготовку к занятиям (изучение лекционного материала, чтение рекомендуемой литературы, ответы на вопросы, выполнение практических заданий и т.д.); - подготовку к итоговой аттестации. В течение семестра по согласованию с преподавателем студент может подготовить реферат или информационное сообщение по теме. Алгоритм проведения круглых столов, диспутов: Регламент проведение круглого стола: 1. Работа Круглого стола строится в форме заседаний и совещаний. 2. Для обеспечения деятельности Круглого стола преподаватель руководит текущей деятельностью, проводит заседание, решает организационные вопросы и осуществляет представительские функции. 3. Регламент ведения заседания: - выступление с докладом - до 10 минут; - выступление в прениях - до 3 минут; - объявление информации - до 1 минуты; 9 4. Для осуществления текущей работы организуется Секретариат Круглого стола (далее Секретариат), который обеспечивает: - подготовку заседаний Круглого стола (оповещение участников, подготовка и тиражирование материалов и др.); - ведение протокола (в случае необходимости - стенограммы) заседания Круглого стола; - подготовку пресс-релизов заседаний Круглого стола. 5. В ходе заседания участники Круглого стола имеют право вносить предложения. 6. По итогам обсуждения Круглого стола принимаются заявления, резолюции и иные документы. Документ считается принятым, если за него проголосовало более половины присутствовавших на заседании участников Круглого стола. Диспут (лат. disputare - рассуждать, спорить) предполагает обсуждение научных и общественно значимых тем. В процессе диспута его участники высказывают свои суждения, дают оценку событиям, рассматривают проблему с различных точек зрения. 1. Процесс проведения диспута состоит из нескольких этапов: выбор темы, назначение руководителя, подбор группы активистов, составление плана проведения диспута, извещение участников о проведении диспута. 2. На подготовительном этапе определение темы для диспута. Она должна быть актуальной и значимой для участников. 3. Обязательным условием выбора темы является ее неоднозначность, то есть то, что может вызвать споры. Составление плана диспута, определив основную проблему и несколько второстепенных вопросов, которые помогут раскрытию темы. 4. В качестве темы диспута обычно выступают судьбоносные события истории, которые по разному освещаются в исторической литературе и вызывают жаркие споры. 5. Разделить аудиторию на условные группы и провести консультации с ними. В каждую группу включите людей с разным уровнем знаний. 6. Ознакомить участников диспута с правилами проведения научного спора – принципами проведения. 7. Начинается диспут с вводного слова, в котором формулируется тема. Определяется регламент выступления всех участников. 8. Направление рассуждения к верным выводам, подталкивание участников к формированию общей позиции по обсуждаемой теме. Отсечение избыточной информации, группировка выводов и сближение точек зрения участвующих в диспуте. 9. Руководство ходом диспута, при необходимости постановка дополнительных вопросов. Помощь в поиске правильного решения. Наблюдение за тем, чтобы диспут не перерос в межличностный конфликт, и обсуждение не зашло в тупик. 10. В конце мероприятия выявление наиболее активных участников диспута. Оценка содержание высказанных мыслей, их умение спорить и аргументировать свои мнения. 11. Подведение итогов диспута, ответ на вопросы, которые не были освещены в процессе выступлений или оказались спорными. Общие принципы проведения: 1. Каждый имеет право высказать свое мнение. Если у тебя есть что сказать слушателям, пусть они узнают это. 2. Говори, что думаешь, думай, что говоришь. Высказывайся ясно и четко. Не утверждай того, в чем не разобрался сам. 3. Постарайся, как можно более убедительно изложить свою точку зрения. Опирайся только на достоверные факты. 4. Не повторяй того, что до тебя было сказано. 5. Уважай чужое мнение. Постарайся понять его. Умей выслушать точку зрения, с которой не согласен. Будь выдержанным. Не перебивай выступающего. Не давай личностных оценок. Правоту доказывай доводами, а не криком. Старайся не навязывать своего мнения. 6. Если доказана ошибочность твоей позиции, имей мужество признать свою неправоту. 7. Пусть главным итогом диспута станет твое продвижение по нелегкому пути постижения истины. 10 Практические задания для самостоятельной работы студентов Примерные тексты для самостоятельной работы студентов Методические рекомендации 1. Прочитайте помещаемую ниже статью " Adaptations to Cold". Сделайте разметку текста для реферативного перевода. Не забывайте, что тот материал, который опускается, должен быть внутри квадратных скобок, а тот, который остается для перевода,— за скобками. Следите за тем, чтобы план части, оставленной для перевода, совпадал с планом оригинальной статьи и чтобы соотношение между логическими составными частями перевода по возможности было таким же, как и соотношение между соответствующими им частями оригинала. Так как объем сокращения в задании не указывается, нужно сокращать до предела, который вы должны определить сами, учитывая важность и сложность содержания, а также особенности стиля в первом значении этого термина (совокупность индивидуальных языковых особенностей автора). Помните, что реферат — это краткое изложение сущности вопроса. Переведите оставленную за скобками часть текста "Adaptations to Cold", обращая особое внимание на сохранение логической связи между отобранными частями. ADAPTATIONS TO COLD by Laurence Irving All living organisms abhor cold. For many susceptible forms of life a temperature difference of a few degrees means the difference between life and death. Everyone knows how critical is temperature for the growth of plants. Insects and fishes are similarly sensitive; a drop of two degrees in temperature when the sun goes behind a cloud, for instance, can convert a f l y from a swift flier to a slow walker. In view of the general hostility of cold to life and activity, the ability of mammals and birds to survive and flourish in all climates is altogether remarkable. It is not that these animals are basically more tolerant to cold. We know from our own reactions how sensitive the human body is to chilling. A naked, inactive human being soon becomes miserable in air colder than 28 degrees Centigrade (about 82 degrees Fa hrenheit), only 10 degrees С below his body temperature. Even in the Tropics the coolness of night can make a person uncomfortable. The discomfort of cold is one of the most vivid of experiences; it stands out as a persistent memory in a soldier's recollections of the unpleasantness of his episodes in the field. The coming of winter in temperate climates has a profound effect on human well-being and activity. Cold weather, or cold living quarters, compounds the misery of illness or poverty. Over the entire planet a large proportion of man's efforts, culture and economy is devoted to the simple necessity of protection against cold. Yet strangely enough neither man nor other mammals have consistently avoided cold climates. Indeed, the venturesome human species often goes out of its way to seek a cold environment, for sport or for the adventure of living in a challenging situation. One of the marvels of man's history is the endurance and stability of the human settlements that have been established in arctic latitudes. The Norse colonists who settled in Greenland 1,000 years ago found Eskimos already living there. Archaeologists today are finding many sites and relics of earlier ancestors of the Eskimos who occupied arctic North America as long as 6,000 years ago. In the middens left by these ancient inhabitants are "bones and hunting implements that indicate man was accompanied in the cold north by many other warm-blooded animals: caribou, moose, bison, bears, hares, seals, walruses and whales. All the species including man, seem to have been well adapted to arctic l i fe for thousands of years. It is therefore a matter of more than idle interest to look closely into how mammals adapt to cold. In all climates and everywhere on the earth mammals maintain a body temperature of about 38 degrees C. It looks as if evolution has settled on this temperature as an optimum for the mammalian class. (In birds the standard body temperature is a few degrees higher.) To keep their internal temperature at a viable level the mammals must be capable of adjusting to a wide range of environmental temperatures. In tropical air at 30 degrees С (86 degrees F), for example, the environment is only eight degrees cooler than the body temperature; in arctic air at — 50 degrees С 11 it is 88 degrees colder. A man or other mammal in the Arctic must adjust to both extremes as seasons change. The mechanisms available for making the adjustments are ( 1 ) the generation of body heat by the metabolic burning of food as fuel and (2) the use of insulation and other devices to retain body heat. The requirements can be expressed quantitatively in a Newtonian formula concerning the cooling of warm bodies. A calculation based on the formula shows that to maintain the necessary warmth of its body a mammal must generate 10 times more heat in the Arctic than in the Tropics or clothe itself in 10 times more effective insulation or employ some intermediate combination of the two mechanisms. We need not dwell on the metabolic requirement; it is rarely a major factor. An animal can increase its food intake and generation of heat to only a very modest degree. Moreover, even if metabolic capacity and the food supply were unlimited, no animal could spend all its time eating. Like man, nearly all other mammals spend a great deal of time in curious exploration of : their surroundings, in play and in family and social activities. In the arctic winter a herd of caribou often rests and ruminates while the young engage in aimless play. I have seen caribou resting calmly with wolves lying asleep in the snow in plain view only a few hundred yards away. There is a common impression that life in the cold climates is more active than in the Tropics, but the fac t is that for the natural populations of mammals, including man, life goes on at the same leisurely peace in the Arctic as it does in warmer regions; in all climates there is the same requirement of rest and social activities. The decisive difference in resisting cold, then, lies in the mechanisms for conserving body heat. In the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska we are continuing studies that have been in progress there and elsewhere for 18 years to compare the mechanisms for conservation of heat in arctic and tropical animals. The investigations have covered a wide variety of mammals and birds and have yielded conclusions of general physiological interest. The studies began with an examination of body insulation. The fur of arctic animals is considerably thicker, of course, than that of tropical animals. Actual measurements showed that its insulating power is many times greater. An arctic fox clothed in its winter fur can rest comfortably at a temperature of — 50 degrees С without increasing its resting rate of metabolism. On the other hand, a tropical animal of the same size (a coati, related to the raccoon) must increase its metabolic effort when the temperature drops to 20 degrees C. That is to say, the fox's insulation is so far superior that the animal can withstand air 88 degrees С colder than its body at resting metabolism, whereas the coati can withstand a difference of only 18 degrees С Naked man is less well protected by natural insulation than the coati; if unclothed, he begins shivering and raising his metabolic rate when the air temperature falls to 28 degrees C. Obviously as animals decrease in size they become less able to carry a thick fur. The arctic hare is about the smallest mammal with enough fur to enable it to endure continual exposure to winter cold. The smaller animals take shelter under the snow in winter. Weasels, for example, venture out of their burrows only for short periods; mice spend the winter in nests and sheltered runways under the snow and rarely come to the surface. No animal, large or small, can cover all of its body with insulating fur. Organs such as the feet, legs and nose must be left unencumbered if they are to be functional. Yet if these extremities allowed the escape of body heat, neither mammals nor birds could survive in cold climates. A gull or duck swimming in icy water would lose heat through its webbed feet faster than the bird could generate it. Warm feet standing on snow or ice would melt it and soon be frozen solidly to the place where they stood. For the unprotected extremities, therefore, nature has evolved a simple but effective mechanism to reduce the loss of heat: the warm outgoing blood in the arteries heats the cool blood returning in the veins from the extremities. This exchange occurs in the rete mirabile (wonderful net), a network of small arteries and veins near the junction between the trunk of the animal and the extremity. Hence the extremities can become much colder than the body without either draining off body heat or losing their ability to function. This mechanism serves a dual purpose. When necessary, the thickly furred animals can use their bare extremities to release excess heat from the body. A heavily insulated animal would 12 soon be overheated by running or other active exercise were it not for these outlets. The generation of heat by exercise turns on the flow of blood to the extremities so that they radiate heat. The large, bare flippers of a resting fur seal are normally cold, but we have found that when these animals on the Pribilof Islands are driven overland at their laborious gait, the flippers become warm. In contrast to the warm flippers, the rest of the fur seal's body surface feels cold, because very little heat escapes through the animal's dense fur. Heat can also be dissipated by evaporation from the mouth and tongue. Thus a dog or a caribou begins to pant, as a means of evaporative cooling, as soon as it starts to run. In the pig the adaptation to cold by means of a variable circulation of heat in the blood achieves a high degree of refinement. The pig, with its skin only thinly covered with bristles, is as naked as a man. Yet it does well in the Alaskan winter without clothing. We can read the animal's response to cold by its expressions of comfort or discomfort, and we have measured its physiological reactions. In cold a i r the circulation of heat in the blood of swine is shunted away from the entire body surface, so that the surface becomes an effective insulator against loss of body heat. The p i g can withstand considerable cooling of its body surface. Although a man is highly uncomfortable when his skin is cooled to 7 degrees С below the internal temperature, a p i g can be comfortable with its skin 30 degrees С colder than the interior, that is, at a temperature of 8 degrees С (about 46 degrees F). Not until the air temperature drops below the freezing point (0 degrees C) does the pig increase its rate of metabolism; in contrast a man, as I have mentioned, must do so at an air temperature of 28 degrees С. With thermocouples in the forms of needles we have probed the tissues of pigs below the skin surface. (Some pigs, like some people, will accept a little pain to win a reward.) We found that with the air temperature at — 12 degrees С the cooling of the pig's tissues extended as deep as 100 millimeters (about four inches) into its body. In warmer air the thermal gradient through the tissues was shorter and less steep. In short, the insulating mechanism of the hog involves a considerable depth of the animal's fatty mantle. Even more striking examples of this kind of mechanism are to be found in whales, walruses and hair seals that dwell in the icy arctic seas. The whale and the walrus are completely bare; the hair seal is covered only with thin, short hair that provides almost no insulation when it is sleeked down in the water. Yet these animals remain comfortable in water around the freezing point although water, with a much greater heat capacity than air, can extract a great deal more heat from a warm body. Examining hair seals from cold waters of the North Atlantic, we found that even in ice water these animals did not raise their rate of metabolism. Their skin was only one degree or so warmer than the water, and the cooling effect extended deep into the tissues — as much as a quarter of the distance through the thick part of the body. Hour after hour the animal's flippers all the way through would remain only a few degrees above freezing without the seals showing any sign of discomfort. When the seals were moved into warmer water, their outer tissues rapidly warmed up. They would accept a transfer from warm water to ice water with equanimity and with no diminution of their characteristic liveliness. How are the chilled tissues of all these animals able to function normally at temperatures close to freezing? There is first of all the puzzle of the response of fatty tissue. Animal fat usually becomes hard and brittle when it is cooled to low temperatures. This is true even of the land mammals of the Arctic, as far as their internal fats are concerned. If it were also true of extremities such as their feet, however, in cold weather their feet would become too inflexible to be useful. Actually it turns out that the fats in these organs behave differently from those in the warm internal tissues. Farmers have known for a long time that neat's-foot oil, extracted from the feet of cattle, can be used to keep leather boots and harness flexible in cold weather. By laboratory examination we have found that the fats in the bones of the lower leg and foot of the caribou remain soft even at 0 degrees C. The melting point of the fats in the leg steadily goes up in the higher portions of the leg. Eskimos have long been aware that fat from a caribou's foot will serve as a fluid lubricant in the cold, whereas the marrow fat from the upper leg is a solid food even at room temperature. 13 About the nonfatty substances in tissues we have little information; I have seen no reports by biochemists on the effects of temperature on their properties. It is known, however, that many of the organic substances of animal, tissues are highly sensitive to temperature. We must therefore wonder how the tissues can maintain their serviceability over the very wide; range of temperatures that the body surface experiences in the arctic climate. We have approached this question by studies of the behaviour of tissues at various temperatures. Nature offers many illustrations of the slowing of tissue functions by cold. Fishes, frogs and water insects are noticeably slowed down by cool water. Cooling by 10 degrees С will immobilize most insects. A grasshopper in the warm noonday sun can be caught only by a swift bird, but in the chill of early morning it is so sluggish that anyone can seize it. I had a vivid demonstration of the temperature effect one summer day when I went hunting on the arctic tundra near Point Barrow for flies to use in experiments. When the sun was behind clouds, I had no trouble picking up the flies as they crawled about in the sparse vegetation, but as soon as the sun came out the flies took off and were uncatchable. Measuring the temperature of flies on the ground, 1 ascertained that the difference between the flying and the slow-crawling state was a matter of only 2 degrees C. Sea-gulls walking barefoot on the ice in the Arctic are just as nimble as gulls on the warm beaches of California. We know from our own sensations that our fingers and hands are numbed by cold. I have used a simple test to measure the amount of this desensitization. After cooling the skin on my fingertips to about 20 degrees С (68 degrees F) by keeping them on ice-filled bags, 1 tested their sensitivity by dropping a light ball (weighing about one milligram) on them from a measured height. The weight multiplied by the distance of fall gave me a measure of the impact on the skin. I found that the skin at a temperature of 20 degrees С was only a sixth as sensitive as at 35 degrees С (96 degrees F); that i s , the impact had to be si x times greater to be felt. We know that even the human body surface has some adaptability to cold. Men who make their living by fishing can handle their nets and fish with wet hands in cold that other people cannot endure. The hands of fishermen, Eskimos and Indians, have been found to be capable of maintaining an exceptionally vigorous blood circulation in the cold. This is possible, however, only at the cost of a higher metabolic production of body heat, and the production in any case has a limit. What must arouse our wonder is the extraordinary adaptability of an animal such as the hair seal. It swims in icy water with its flippers and the skin over its body at close to the freezing temperature, and yet under the ice in the dark Arctic sea it remains sensitive enough to capture moving prey and find its way to breathing holes. Here lies an inviting challenge for all biologists. By what devices is an animal able to preserve nervous sensitivity in tissues cooled to low temperatures? Beyond this is a more universal and more interesting question: How do the warm-blooded animals preserve their overall stability in the varying environment to which they are exposed? Adjustment to changes in temperature requires them to make a variety of adaptations in the various tissues of the body. Yet these changes must be harmonized to maintain the integration of the organism as a whole. 2. Сделайте аннотационный перевод помещаемой ниже статьи “The Origin of Man”. Объем аннотации – не более 600 печатных знаков THE ORIGIN OF MAN Although the Darwin — Mendel — De Vries theory of evolution provides a general frame for understanding the emergence of man, it leaves open crucial questions of detail. Why have man, and, to a lesser extent, the higher apes so strikingly exceeded other animals in intellectual development? Or can one recognize distinct turning points of the development? A well-known fact of physiology, the possible evolutionary significance of which does not seem to have received attention, points strongly towards the second alternative. Mammals are distinguished from other vertebrates and from insects by their ability to produce the enzyme uricase, which oxidizes uric acid to allantoin by breaking up its purine ring according to the scheme. 14 The only exceptions to this are man and the higher apes, which have lost the capacity for synthesizing uricase and which, therefore, end the metabolism and catabolisrn of nucleoproteins with uric acid, instead of carrying it on to allantoin. Until recently, the Dalmatian dog (coach-hound) was also thought to be an exception. However, it has been found that this animal does possess sufficient amounts of uricase; it excretes uric acid merely because, owing to the effect of a simple recessive gene, no tubular re-absorption of uric acid from the glomerular filtrate takes place in its kidneys. Uric acid had two remarkable properties. It is very sparingly, soluble in water; meat-eating animals that lack uricase, therefore, have to maintain a steady high concentration of uric acid in their blood in order to eliminate the amount they produce. Moreover, uric acid, in common with other purines such as caffeine or theobromine, is a cerebral stimulant. Consequently, animals that eat nucleoproteins but lack uricase are under constant influence of a powerful stimulant. This circumstance may have played a decisive part in the intellectual development of the higher primates. The selective value of a small beneficial mutation of the associative mechanism of the brain must be very small, unless the animal uses its brain even when this is not urgently necessary; that is, unless it thinks about past experiences and future possibilities in times when there is no acute need for thinking. Such a tendency to philosophical reflexion must be very unusual in animals; even modern man has, in general, no irresistible addiction to mental work. A beneficial mutation of the associative mechanism of the brain, therefore, has only a poor chance of establishing itself in the species unless its selective value is strongly enhanced by the action of a cerebral stimulant such as is uric acid. The mutations that have led to the loss of uricase, then, may have been a crucial step on the way to the development of man. In all probability the loss of uricase was not a sudden event due to a single mutation. Some monkeys seem to show a slightly impaired capacity for uricase production: this suggests a gradual assembly of the gene-constellation that has ultimately led to the almost complete absence of uricase. In the lower mammals, this assembly did not progress beyond a primitive stage, because the higher brain functions were relatively undeveloped, and the effects of their stimulation by uric acid could not counterbalance the physiological disadvantages of this compound. From a certain stage of the brain development onwards, however, the increment of viability due to uric acid must have changed its sign from negative to positive, and then the assembly of the uricase loss gene-constellation could progress hand in hand with the accelerated development of the brain due to the increasing level of uric acid concentration. Can the viability-increment due to a stimulant be large enough to cause such momentous developments? Millions of the present generation owe their careers, and some even their lives, to caffeine or theobromine, taken during preparation for an examination, a negotiation, or during a strenuous cardrive. Uric acid, of course, is not so effective as coffee or tea, but its effect as a catalyser of mental development has extended over a million years, starting probably long before the Oligocene branching of the great orthograde primates. A widespread popular opinion associates the vigour and initiative of the populations of the wealthy industrial areas with their high meat consumption. In fact, it is quite likely that the 'pressure-of-life' diseases prevalent in the highly industrialized areas are, to a considerable extent, 'pressure-of-uric acid' diseases. Although not so effective as caffeine or theobromine, this stimulant can be a more powerful inhibitor of rest and recovery from work by its action extending over day and night. 3. Сделайте полный письменный перевод статьи с русского языка на английский. Учитывайте контекст статьи. Обращайте внимание на термины. Помните, что заголовок переводится в последнюю очередь. Отредактируйте перевод. Нью-Йорк может уйти под воду Расположенный близко к уровню моря американский мегаполис может уйти под воду в течение ближайших ста лет. Об этом предупредили ученые Университета штата Флорида, изучающие последствия глобального потепления. Нью-Йорк расположен на островах и находится в среднем на отметке пяти метров над уровнем океана. При этом береговая линия Манхэттена в некоторых местах расположена всего лишь на 1,5 метра выше этого уровня. Таким образом, риск быть затопленным для Нью-Йорка намного больше, чем для других прибрежных мегаполисов - Лондона, Токио, Сиднея, Майами или Сан-Франциско. 15 В то же время ученые полагают, что в ближайшие 100 лет уровень Атлантического океана значительно повысится из-за таяния льдов Гренландии и Антарктики. К 2100 году уровень Атлантики повысится на 51 сантиметр, что усилит риск наводнений не только для Нью-Йорка, но также для Вашингтона и Бостона. В свою очередь китайские ученые предупреждают о негативных последствиях глобального потепления для своей страны. Территория Китая быстро уходит под воду и процесс повышения уровня моря у Китая идет быстрее, чем в среднем по миру. Только за 2007 год уровень моря у китайских берегов поднялся на 2,5 миллиметра, тогда как среднемировой показатель составил 1,8 миллиметра. В наибольшей мере приближение стихии заметно у берегов Желтого моря, в районе города Тяньцзинь: там уровень воды поднялся на 196 миллиметров. Второе место занимает район Шанхая в Восточно-Китайском море, где берега опустились на 115 миллиметров. Отметим, что недавно немецкие климатологи предсказали критическое повышение температуры уже через 10 лет. По их прогнозам, в летние месяцы температура на улицах городов станет смертельной для престарелых и больных людей. 4. Сделайте полный письменный перевод статьи с английского языка на русский. Учитывайте контекст статьи. Обращайте внимание на термины. Помните, что заголовок переводится в последнюю очередь. Отредактируйте перевод. Stem cells 'created from teeth' Japanese scientists say they have created human stem cells from tissue taken from the discarded wisdom teeth of a 10-year-old girl. The researchers say their work suggests that wisdom teeth could be a suitable alternative to human embryos as a source for therapeutic stem cells. Research involving stem cells is seen as having the potential to treat many life-threatening diseases. But some people do not believe it is morally right to use human embryos. The researchers, based at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), say it will be at least five years before their findings result in practical medical applications. Stem cells have the ability to develop into other kinds of human cells, and experts believe they may eventually lead to treatments for some of the most intractable conditions, such as cancer and diabetes. The AIST researchers said they had identified a form of stem cell in the wisdom teeth which had the capability to develop and be grown successfully into other forms of cell outside the body. The cells they harvested continued to grow in the laboratory for just over a month, they added. The leader of the team, Hajime Ogushi, said the research was significant in two ways. "One is that we can avoid the ethical issues of stem cells because wisdom teeth are destined to be thrown away anyway," he told the AFP news agency. "Also, we used teeth that had been extracted three years ago and had been preserved in a freezer. That means that it's easy for us to stock this source of stem cells." In the US, dentists are starting to offer to store stem cells taken from wisdom teeth and from baby teeth, another potential source, for therapeutic purposes in the future. Last year, a team of US and Japanese scientists announced they had managed to produce stem cells from skin. 12.Формы промежуточного и итогового контроля Образцы тестовых заданий для промежуточного контроля по курсу «Аннотирование и реферирование» Вариант 1 1. Приведите особенности научно-технического текста. 2. Одной из особенностей художественного текста является: А. использование терминов; Б. использование стилистических средств; В. краткость изложения. 16 3. __________________ - это перевод, используемый для обмена специальной научно-технической информацией между людьми, говорящими на разных языках. 4. __________________ - это полный письменный перевод заранее отобранных частей оригинала, составляющих связный текст. 5. Из всех видов технического перевода основной формой является: А. аннотационный перевод; Б. полный письменный перевод; В. перевод типа «экспресс-информация». 6. Объем аннотационного перевода составляет: А. половину объема текста оригинала; Б. не более 800 печатных знаков; В. не более 500 печатных знаков. 7. Существуют два вида аннотаций, которые должен уметь составлять технический переводчик. Назовите их. А. Б. 8. Разметка текста при реферативном переводе осуществляется с помощью: А. квадратных скобок; Б. круглых скобок; В. горизонтальных линий. 9. Назовите три потока поступления научно-технической информации: А. Б. В. 10. Перевод заголовков патентов - это ______________________________. 11. Патент состоит из: А. Б. В. Г. Д. Е. 12. Последовательный перевод может быть: А. Б. 13. Одним из способов введения нового термина является: А. калькирование; Б. антонимический перевод; В. переводчик не имеет права вводить новый термин. 14. Краткое изложение сущности какого-либо вопроса это – А. пересказ; Б. аннотация; В. реферат. 15. Соотнесите значение термина «valve» с областью техники, в которой он используется: 1. электронная лампа; А. теплотехника; 2. кран; Б. медицина; 3. клапан сердца. В. радиотехника. 16. Первым этапом работы над переводом является: А. редактирование; Б. ознакомление с оригиналом; В. черновой перевод. 17 Вариант 2 1. Приведите особенности художественного текста. 2. Одной из особенностей научно-технического текста является: А. использование большого количества терминов; Б. использование большого количества реалий; В. метонимия. 3. __________________ - это выражение того, что уже было выражено на одном языке, средствами другого языка. 4. __________________ - это вид технического перевода, заключающийся в составлении аннотации оригинала на другом языке. 5. Основная форма обмена специальной научно технической информацией – А. патентная литература; Б. отраслевой словарь; В. электронные письма. 6. Реферативный перевод должен быть короче оригинала в: А. 2 раза; Б. не должен быть значительно короче; В. 5 – 10 раз. 7. В аннотацию специальной статьи или книги может входить: А. Б. 8. Главное отличие аннотации статьи или книги это: А. абстрагированное выражение идеи; Б. характеристик оригинала; В. критика оригинала. 9. Назовите три формы составления реферата, которым соответствуют три самостоятельных вида технического перевода: А. Б. В. 10. Аннотационный перевод патентов – это _________________________. 11. Консультативный перевод включает: А. Б. В. Г. 12. Назовите виду устного перевода, используемого для обмена научно-технической информацией: А. Б. В. 13. Если слово не найдено не в одном источнике информации, но смысл его ясен из контекста, переводчик имеет право: А. его не переводить; Б. после консультации со специалистом предложить новый термин; В. заменить схожим термином. 14. Реферативный перевод считается: А. сокращенным видом перевода; Б. полным письменным переводом; 18 В. устным переводом. 15. Соотнесите значение термина «frame» с областью техники, в которой он используется: 1. каркас; А. кинематография; 2. кадр; Б. строительств; 3. ткацкий станок. В. текстильное производство. 16. Заголовок всегда переводится: А. в последнюю очередь; Б. в первую очередь; В. по желанию переводчика. Вопросы для подготовки к зачету 1. Дайте определение понятия "текст" и кратко опишите его внешнюю структуру. 2. Каковы формы выражения мысли в тексте? 3. Каковы особенности научно-технического и художественного текста? 4. Опишите типы межфразовых связей. 5. Расскажите о логическом развитии мысли в тексте. 6. Что такое лексическая тематическая основа текста? 7. Как работать с заголовком? 8. Дайте понятие сегментации текста. 9. Назовите типы сверхфразовых единств. 10. Опишите субтекст и его разновидности. 11. Кратко опишите внутреннюю структуру текста. 12. Дайте определение понятия "тема" и “рема”. 13. Дайте понятие импликации как грамматического явления. 14. Подтекст и способы его формирования. 15. Что такое “семантическое свертывание текста”? 16. Проблема ядерного текста и избыточность. 17. Каковы приемы использования опоры на внешнюю и внутреннюю структуру текста? 18. Расскажите о типологии текстов и межфразовых связях. 19. Индуктивный подход к работе с текстом. Принцип перехода от внешней текстовой структуры к внутренней. 20. Какова методика извлечения имплицитного смысла? 21. Как выявить подтекст в художественном произведении? 22. Каковы приемы визуального моделирования смысловой структуры целого текста? 23. Формулирование ядерного высказывания: тема текста, рема текста. 24. Смысловое свертывание при реферировании текста. 25. Что такое реферат теста? 26. Назовите алгоритм составления реферата текста. 27. Что такое аннотация теста? 28. Назовите алгоритм составления аннотации текста. 29. Дайте характеристику других видов операций по свертыванию текста: пересказ текста, адаптация текста, реферативный перевод. 30 Что такое перевод патентов? 31. Виды устного сокращенного перевода. Практическое задание по составлению реферата или аннотации текста. 19