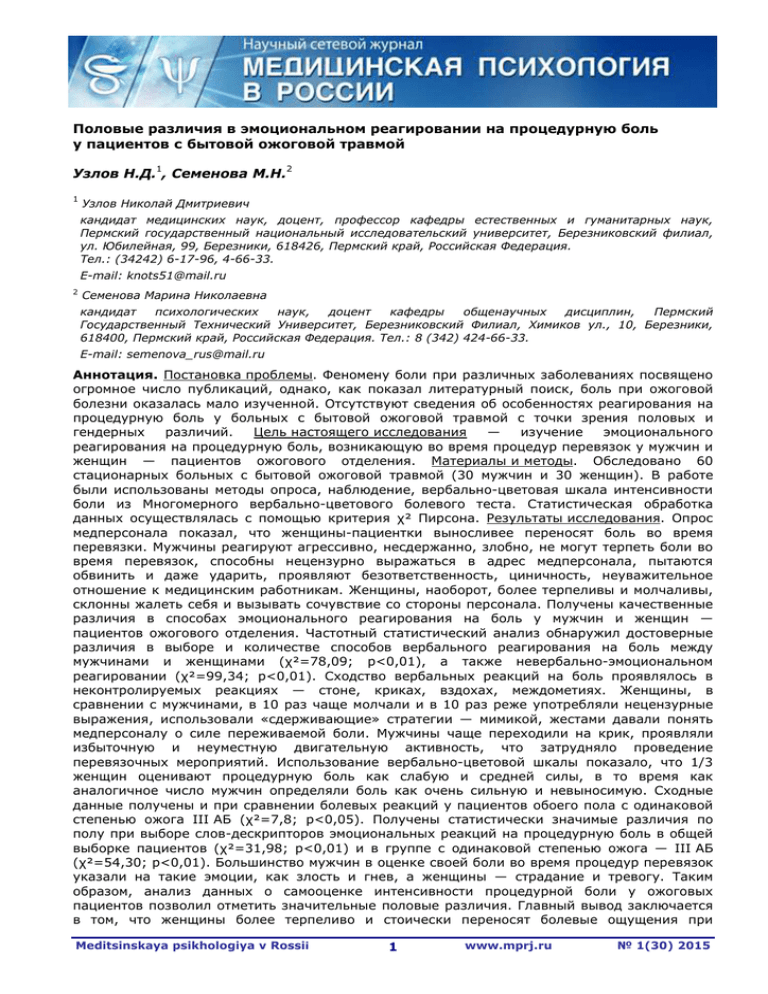

Половые различия в эмоциональном реагировании на

advertisement