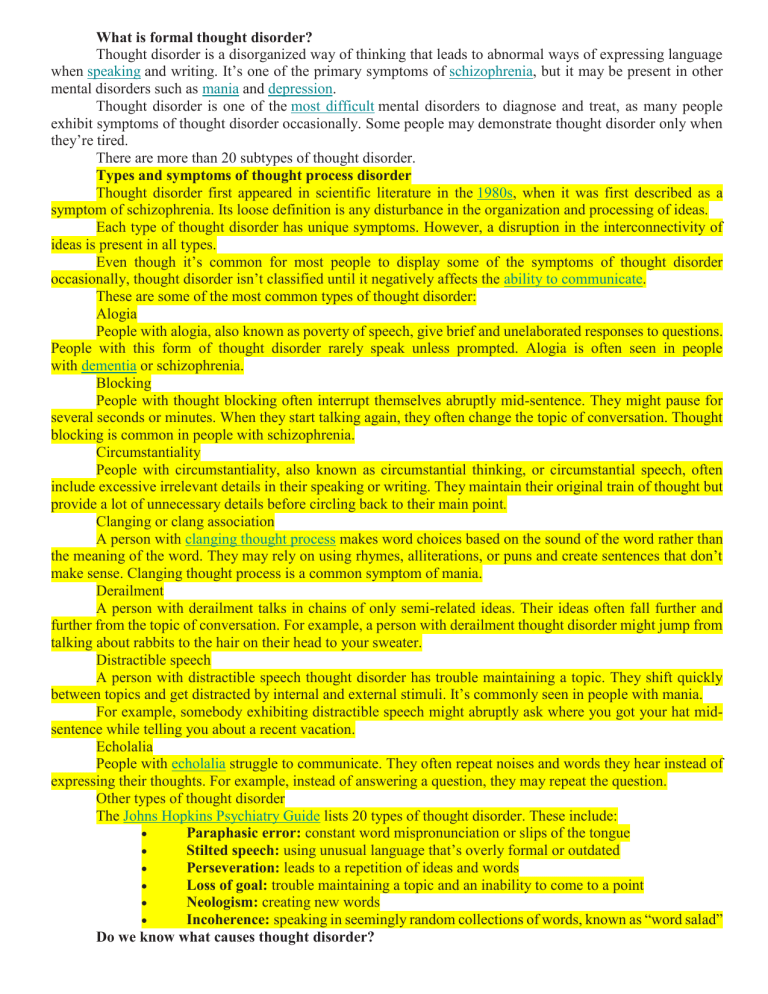

What is formal thought disorder? Thought disorder is a disorganized way of thinking that leads to abnormal ways of expressing language when speaking and writing. It’s one of the primary symptoms of schizophrenia, but it may be present in other mental disorders such as mania and depression. Thought disorder is one of the most difficult mental disorders to diagnose and treat, as many people exhibit symptoms of thought disorder occasionally. Some people may demonstrate thought disorder only when they’re tired. There are more than 20 subtypes of thought disorder. Types and symptoms of thought process disorder Thought disorder first appeared in scientific literature in the 1980s, when it was first described as a symptom of schizophrenia. Its loose definition is any disturbance in the organization and processing of ideas. Each type of thought disorder has unique symptoms. However, a disruption in the interconnectivity of ideas is present in all types. Even though it’s common for most people to display some of the symptoms of thought disorder occasionally, thought disorder isn’t classified until it negatively affects the ability to communicate. These are some of the most common types of thought disorder: Alogia People with alogia, also known as poverty of speech, give brief and unelaborated responses to questions. People with this form of thought disorder rarely speak unless prompted. Alogia is often seen in people with dementia or schizophrenia. Blocking People with thought blocking often interrupt themselves abruptly mid-sentence. They might pause for several seconds or minutes. When they start talking again, they often change the topic of conversation. Thought blocking is common in people with schizophrenia. Circumstantiality People with circumstantiality, also known as circumstantial thinking, or circumstantial speech, often include excessive irrelevant details in their speaking or writing. They maintain their original train of thought but provide a lot of unnecessary details before circling back to their main point. Clanging or clang association A person with clanging thought process makes word choices based on the sound of the word rather than the meaning of the word. They may rely on using rhymes, alliterations, or puns and create sentences that don’t make sense. Clanging thought process is a common symptom of mania. Derailment A person with derailment talks in chains of only semi-related ideas. Their ideas often fall further and further from the topic of conversation. For example, a person with derailment thought disorder might jump from talking about rabbits to the hair on their head to your sweater. Distractible speech A person with distractible speech thought disorder has trouble maintaining a topic. They shift quickly between topics and get distracted by internal and external stimuli. It’s commonly seen in people with mania. For example, somebody exhibiting distractible speech might abruptly ask where you got your hat midsentence while telling you about a recent vacation. Echolalia People with echolalia struggle to communicate. They often repeat noises and words they hear instead of expressing their thoughts. For example, instead of answering a question, they may repeat the question. Other types of thought disorder The Johns Hopkins Psychiatry Guide lists 20 types of thought disorder. These include: Paraphasic error: constant word mispronunciation or slips of the tongue Stilted speech: using unusual language that’s overly formal or outdated Perseveration: leads to a repetition of ideas and words Loss of goal: trouble maintaining a topic and an inability to come to a point Neologism: creating new words Incoherence: speaking in seemingly random collections of words, known as “word salad” Do we know what causes thought disorder? The cause of thought disorder isn’t well known. Thought disorder isn’t a symptom of any particular disorder, but it’s commonly seen in people with schizophrenia and other mental health conditions. The cause of schizophrenia also isn’t known, but it’s thought that biological, genetic, and environmental factors can all contribute. Thought disorder is loosely defined and the symptoms vary widely, so it’s difficult to find a single underlying cause. Researchers are still debating about what might lead to the symptoms of thought disorder. Some believe it might be caused by changes in language-related parts of the brain, while others think it could be caused by problems in more general parts of the brain. Content-thought disorder Content-thought disorder is a thought disturbance in which a person experiences multiple, fragmented delusions, typically a feature of schizophrenia, and some other mental disorders including obsessive–compulsive disorder, and mania.[18][4] At the core of thought content disturbance are abnormal beliefs and convictions, after accounting for the person's culture and backgrounds, and range from overvalued ideas to fixed delusions.[19] Typically, abnormal beliefs and delusions are non-specific diagnostically,[20] even if some delusions are more prevalent in one disorder than another.[21] Also neurotypical thought—consisting of awareness, concerns, beliefs, preoccupations, wishes, fantasies, imagination, and concepts—can be illogical, and can contain beliefs and prejudices/biases that are obviously contradictory.[22][23] Individuals also have considerable variations, and the same person's thinking also may shift considerably from time to time.[24] Content-thought disorder is not limited to delusions. Other possible abnormalities include suicidal ideas, violent ideas, and homicidal ideas[25] as well as the following: Preoccupation centering thought to a particular idea in association with strong affection Obsession a persistent thought, idea, or image that is intrusive or inappropriate, and is distressing or upsetting Compulsive behavior the need to perform an act persistently and repetitively—without it necessarily leading to an actual reward or pleasure—to reduce distress Magical thinking belief that one's thoughts by themselves can bring about effects in the world, or that thinking something corresponds with doing the same thing Overvalued ideas false or exaggerated belief that is held with conviction but not with delusional intensity Phobias irrational fears of objects or circumstances In psychosis, delusions are the most common thought-content abnormalities. A delusion is a firm and fixed belief based on inadequate grounds not amenable to rational argument or evidence to the contrary, and not in sync with regional, cultural and educational background. Delusions are common in people with mania, depression, schizoaffective disorder, delirium, dementia, substance use disorder, schizophrenia, and delusional disorders. Common examples in mental status examination include the following:[27] Erotomania belief that someone is in love with oneself Grandiose delusions belief that one is the greatest, strongest, fastest, richest, and/or most intelligent person ever Persecutory delusion belief that the person, or someone to whom the person is close, is being malevolently treated in some way Ideas of reference and delusions of reference belief that insignificant remarks, coincident events, or innocuous objects in one's environment have personal meaning or significance Thought broadcasting belief that others can hear or are aware of one's thoughts Thought insertion belief that one's thoughts are not one's own, but rather belong to someone else and have been inserted into one's mind[30] Thought withdrawal belief that thoughts have been 'taken out' of one's mind, and one has no power over this Influence belief that other people or external agents are covertly exerting powers over oneself Outside control belief that outside forces are controlling one's thoughts, feelings, and actions[31] Infidelity belief that a partner is cheating on oneself Somatic belief that one has a disease or medical condition Nihilistic belief that the mind, body, the world at large, or parts thereof, no longer exist Types There are many types of thought disorder.[37] They are also referred to as symptoms of formal thought disorder of which 30 are described including:[12] Alogia (also poverty of speech) A poverty of speech, either in amount or content. Under negative/positive symptom classification of schizophrenia, it is classified as a negative symptom. When classifying symptoms into more dimensions, poverty of speech content—paucity of meaningful content with normal amount of speech—is a disorganization symptom, whereas poverty of speech—loss of speech production—is a negative symptom.[38] Under SANS, thought blocking is considered a part of alogia, and so is increased latency in response.[39] Blocking or thought blocking (also deprivation of thought and obstructive thought) An abrupt stop in the middle of a train of thought which may or not be able to be continued.[40] Circumstantial speech (also circumstantial thinking)[41] An inability to answer a question without giving excessive, unnecessary detail.[42] This differs from tangential thinking, in that the person does eventually return to the original point. For example, the patient answers the question "how have you been sleeping lately?" with "Oh, I go to bed early, so I can get plenty of rest. I like to listen to music or read before bed. Right now I'm reading a good mystery. Maybe I'll write a mystery someday. But it isn't helping, reading I mean. I have been getting only 2 or 3 hours of sleep at night."[43] Clanging A severe form of flight of ideas whereby ideas are related only by similar or rhyming sounds rather than actual meaning.[44][45] This may be heard as excessive rhyming and/or alliteration. e.g. "Many moldy mushrooms merge out of the mildewy mud on Mondays." "I heard the bell. Well, hell, then I fell." It is most commonly seen in bipolar disorder (manic phase), although it is often observed in patients with primary psychoses, namely schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Derailment (also loose association and knight's move thinking)[41] Thought frequently moves from one idea to another which is obliquely related or unrelated, often appearing in speech but also in writing,[46] e.g. "The next day when I'd be going out you know, I took control, like uh, I put bleach on my hair in California."[47] Distractible speech During mid speech, the subject is changed in response to a nearby stimulus. e.g. "Then I left San Francisco and moved to... Where did you get that tie?"[48][49] Echolalia[50] Echoing of another's speech[44] that may only be committed once, or may be continuous in repetition. This may involve repeating only the last few words or last word of the examiner's sentences. This can happen immediately after a stimuli, or months to years later.[50] Echolalia is commonly seen with Autism and Tourette's Syndrome, though, there are plenty of disorders that it can be attributed to.[51][52][53] e.g. "What would you like for dinner?", "What would you like for dinner?" "That's a good question." "That's a good question." Evasion The next logical idea in a sequence is replaced with another idea closely but not accurately or appropriately related to it. Also called paralogia and perverted logic.[54][55] Example: "I... er ah... you are uh... I think you have... uh-- acceptable erm... uh... hair." Flight of ideas[41] A form of formal thought disorder marked by abrupt leaps from one topic to another, possibly with discernable links between successive ideas, perhaps governed by similarities between subjects or, in somewhat higher grades, by rhyming, puns, and word plays, or by innocuous environmental stimuli – e.g., the sound of birds chirping. It is most characteristic of the manic phase of bipolar illness.[44] Illogicality[56] Conclusions are reached that do not follow logically (non-sequiturs or faulty inferences). e.g. "Do you think this will fit in the box?" draws a reply like "Well duh; it's brown, isn't it?" Incoherence or word salad[41] Speech that is unintelligible because, though the individual words are real words, the manner in which they are strung together results in incoherent gibberish,[44] e.g. the question "Why do people comb their hair?" elicits a response like "Because it makes a twirl in life, my box is broken help me blue elephant. Isn't lettuce brave? I like electrons, hello please!" Neologisms[41] forms completely new words or phrases whose origins and meanings are usually unrecognizable. Example is "I got so angry I picked up a dish and threw it at the geshinker." [57] These may also involve elisions of two words that are similar in meaning or in sound.[58] Although neologisms may sometimes refer to words that are formed incorrectly but whose origins are understandable (e.g. "headshoe" for hat), these can be more clearly referred to as word approximations.[59] Overinclusion[50] The failure to eliminate ineffective, inappropriate, irrelevant, extraneous details associated with a particular stimulus.[28][60] Perseveration[50] Persistent repetition of words or ideas even when another person attempts to change the topic.[44] e.g. "It's great to be here in Nevada, Nevada, Nevada, Nevada, Nevada." This may also involve repeatedly giving the same answer to different questions. e.g. "Is your name Mary?" "Yes." "Are you in the hospital?" "Yes." "Are you a table?" "Yes." Perseveration can include palilalia and logoclonia, and can be an indication of organic brain disease such as Parkinson's.[50] Phonemic paraphasia Mispronunciation; syllables out of sequence. e.g. "I slipped on the lice and broke my arm."[61] Pressured speech[62] Rapid speech without pauses, difficult to interrupt. Referential thinking "Patients tendency to view innocuous stimuli as having a specific meaning for the self."[63] This could be seen as them repeatedly and inappropriately referring back to self. e.g. "What's the time?", "It's 7 o'clock. That's my problem." Semantic paraphasia Substitution of inappropriate word. e.g. "I slipped on the coat, on the ice I mean, and broke my book."[64] Stilted speech[65] Sentences may be stilted or vague. Speech characterized by the use of words or phrases that are flowery, excessive, and pompous,[44] e.g. "The attorney comported himself indecorously." Tangential speech Wandering from the topic and never returning to it or providing the information requested.[44][66] For example, in answer to the question "Where are you from?", the person answers "My dog is from England. They have good fish and chips there. Fish breathe through gills." Verbigeration[67] Meaningless and stereotyped repetition of words or phrases replacing understandable speech, as seen in schizophrenia. What is Intellectual Disability? Intellectual disability1 involves problems with general mental abilities that affect functioning in two areas: o o intellectual functioning (such as learning, problem solving, judgement) adaptive functioning (activities of daily life such as communication and independent living) Additionally, the intellectual and adaptive deficity begin early in the developmental period. Intellectual disability affects about 1% of the population, and of those about 85% have mild intellectual disability. Males are more likely than females to be diagnosed with intellectual disability. Diagnosing Intellectual Disability Intellectual disability is identified by problems in both intellectual and adaptive functioning. Intellectual functioning is measured with individually administered and psychometrically valid, comprehensive, culturally appropriate, psychometrically sound tests of intelligence. While a specific full-scale IQ test score is no longer required for diagnosis, standardized testing is used as part of diagnosing the condition. A full-scale IQ score of around 70 to 75 indicates a significant limitation in intellectual functioning. 2 However, the IQ score must be interpreted in the context of the person’s difficulties in general mental abilities. Moreover, scores on subtests can vary considerably so that the full-scale IQ score may not accurately reflect overall intellectual functioning. Therefore, clinical judgment is needed in interpreting the results of IQ tests. . Three areas of adaptive functioning are considered: 1. Conceptual – language, reading, writing, math, reasoning, knowledge, memory 2. Social – empathy, social judgment, communication skills, the ability to follow rules and the ability to make and keep friendships 3. Practical – independence in areas such as personal care, job responsibilities, managing money, recreation, and organizing school and work tasks Adaptive functioning is assessed through standardized measures with the individual and interviews with others, such as family members, teachers and caregivers. Intellectual disability is identified as mild (most people with intellectual disability are in this category), moderate or severe. The symptoms of intellectual disability begin during childhood. Delays in language or motor skills may be seen by age two. However, mild levels of intellectual disability may not be identified until school age when a child has difficulty with academics. Causes There are many different causes of intellectual disability. It can be associated with a genetic syndrome, such as Down syndrome or Fragile X syndrome. It may develop following an illness such as meningitis, whooping cough or measles; may result from head trauma during childhood; or may result from exposure to toxins such as lead or mercury. Other factors that may contribute to intellectual disability include brain malformation, maternal disease and environmental influences (alcohol, drugs or other toxins). A variety of laborand delivery-related events, infection during pregnancy and problems at birth, such as not getting enough oxygen, can also contribute. Treatment Intellectual disability is a life-long condition. However, early and ongoing intervention may improve functioning and enable the person to thrive throughout their lifetime. Underlying medical or genetic conditions and co-occurring conditions frequently add to the compplex lives of people with intellectual disability. Once a diagnosis is made, help for individuals with intellectual disability is focused on looking at the individual’s strengths and needs, and the supports he or she needs to function at home, in school/work and in the community. Services for people with intellectual disabilities and their families can provide support to allow full inclusion in the community. Many different types of supports and services can help, such as: o Early intervention (infants and toddlers) o Special education o Family support (for example, respite care support groups for families) o Transition services from childhood to adulthood o Vocational programs o Day programs for adults o Housing and residential options o Case management Under federal law (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA, 1990), early intervention services work to identify and help infants and toddlers with disabilities. Federal law also requires that special education and related services are available free to every eligible child with a disability, including intellectual disability. In addition, supports can come from family, friends, co-workers, community members, school, a physician team, or from a service system. Job coaching is one example of a support that can be provided by a service system. With proper support, people with intellectual disabilities are capable of successful, productive roles in society. A diagnosis often determines eligibility for services and protection of rights, such as special education services and home and community services. The American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) stresses that the main reason for evaluating individuals with intellectual disabilities is to be able to identify and put in place the supports and services that will help them thrive in the community throughout their lives. Related and co-occurring conditions Some mental health, neurodevelopmental, medical and physical conditions frequently co-occur in individuals with intellectual disability, including autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder, impulse control disorder, and depression and anxiety disorders. Identifying and diagnosing co-occurring conditions can be challenging, for example recognizing depression in an individual with limited verbal ability. Family caregivers are very important in identifying subtle changes. An accurate diagnosis and treatment are important for a healthy and fulfilling life for any individual. What is an intellectual disability? An intellectual disability is characterised by someone having an IQ below 70 (the median IQ is 100), as well as significant difficulty with daily living such as self-care, safety, communication, and socialisation. People with an intellectual disability may process information more slowly, find communication and daily living skills hard, and also have difficulty with abstract concepts such as money and time. An intellectual disability may be caused by a genetic condition, problems during pregnancy and birth, health problems or illness, and environmental factors. Types of intellectual disabilities Fragile X syndrome Fragile X syndrome is the most common known cause of an inherited intellectual disability worldwide. It is a genetic condition caused by a mutation (a change in the DNA structure) in the X chromosome. People born with Fragile X syndrome may experience a wide range of physical, developmental, behavioural, and emotional difficulties, however, the severity can be very varied. Some common signs include a developmental delay, intellectual disability, communication difficulties, anxiety, ADHD, and behaviours similar to autism such as hand flapping, difficulty with social interactions, difficulty processing sensory information, and poor eye contact (Better Health). Boys are usually more affected than girls – it affects around 1 in 3,600 boys and between 1 in 4,000 – 6,000 girls (Better Health). Down syndrome Down syndrome is not a disease or illness, it is a genetic disorder which occurs when someone is born with a full, or partial, extra copy of chromosome 21 in their DNA. Down syndrome is the most common genetic chromosomal disorder and cause of learning disabilities in children (Mayo Clinic). In Australia, approximately 270 children, or one in 1,100, are born with Down syndrome each year. People with Down syndrome can have a range of common physical and developmental characteristics as well as a higher than normal incidence of respiratory and heart conditions. Physical characteristics associated with Down syndrome can include a slight upward slant of the eyes, a rounded face, and a short stature. People may also have some level of intellectual and learning disabilities, but this can be quite different from person to to another. Developmental delay When a child develops at a slower rate compared to other children of the same age, they may have a developmental delay. One or more areas of development may be affected including their ability to move, communicate, learn, understand, or interact with other children. Sometimes children with a developmental delay may not talk, move or behave in a way that’s appropriate for their age but can progress more quickly as they grow. For others, their developmental delay may become more significant over time and can affect their learning and education. Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder which affects around 1 in 10,000 – 20,000 people (Better Health Channel). This disability is quite complex and it’s caused by an abnormality in the genes of chromosome 15. One of the most common symptoms of PWS is a constant and insatiable hunger which typically begins at two years of age. People with PWS have an urge to eat because their brain (specifically their hypothalamus) won’t tell them that they are full, so they are forever feeling hungry. The symptoms of PWS can be quite varied, but poor muscle tone and a short stature are common. A level of intellectual disability is also common, and children can find language, problem solving, and maths difficult. Someone with PWS may also be born with distinct facial features including almond-shaped eyes, a narrowing of the head, a thin upper-lip, light skin and hair, and a turned-down mouth. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) FASD refers to a number of conditions that are caused when an unborn foetus is exposed to alcohol. When a mother is pregnant, alcohol crosses the placenta from the mother’s bloodstream into the baby’s, exposing the baby to similar concentrations as the mother (Better Health Channel). The symptoms can vary however can include distinctive facial features, deformities of joints, damage to organs such as the heart and kidneys, slow physical growth, learning difficulties, poor memory and judgement, behavioural problems, and poor social skills. Many cases are also often misdiagnosed as autism or ADHD as they can have similarities. The World Health Organisation recommends that mothers-to-be, or those planning on conceiving, should completely abstain from alcohol. Environmental and other causes Sometimes an intellectual disability is caused by an environmental factor or other causes. These causes can be quite varied but can include: Problems during pregnancy such as viral or bacterial infections Complications during birth Exposure to toxins such as lead or mercury Complications from illnesses such as meningitis, measles or whooping cough Malnutrition Exposure to alcohol and other drugs Trauma And even unknown causes Sex Males are more likely than females to be diagnosed with ID. According to the National Health Interview Survey, from 1997 to 2008 the prevalence of ID was 0.78 percent in boys and 0.63 percent in girls (Boyle et al., 2011). Overall, studies of prevalence show a male excess in the prevalence of ID, which is partially explained by x-linked causes of the disability, such as fragile X syndrome (Durkin et al., 2007). Socioeconomic Status Poverty is one of the most consistent risk factors for ID (Cooper and Lackus, 1983; Durkin et al., 1998; Stein and Susser, 1963). Boyle and colleagues reported that in the United States between 1997 and 2008, the prevalence of ID among children below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) was 1.03 percent, while for those above 200 percent FPL the rate was 0.5 percent (Boyle et al., 2011). Similarly, Camp and colleagues found the prevalence of ID among children of low SES to be more than twice as high as that among middle- or high-SES children (Camp et al., 1998). The association between low SES and poverty is considerably stronger for mild than for more severe levels of ID (Drews et al., 1995; Durkin et al., 1998). FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT The diagnosis of ID requires evidence of impairments in real life (adaptive) skills; thus all people with ID demonstrate functional impairment. These adaptive abilities relate to such things as understanding rules, the ability to navigate the tasks of daily living, and participation in family, school, and community activities. Various assessments of such skills are available, such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales which is a widely used instrument (Sparrow et al., 2005). Assessment of these skills helps to plan remediation, i.e., teaching specific skills and working on generalization of skills. FINDINGS Historically, intellectual disability has been defined by significant cognitive deficits, typically established by the testing of IQ and adaptive behaviors. There are no laboratory tests for ID; however, many specific causes and genetic factors for ID can be identified through laboratory tests. Males are more likely than females to be diagnosed with ID. Poverty is a risk factor for ID, especially for mild ID. The functional impairments associated with ID are generally lifelong. However, there are functional supports that may enable an individual with ID to function well and participate in society. As a diagnostic category, IDs include individuals with a wide range of intellectual functional impairments and difficulties with daily life skills. The levels of severity of intellectual impairment and the need for support can vary from profound to mild. Comorbidities, including behavioral disorders, are common. Treatment usually consists of appropriate education and skills training, supportive environments to optimize functioning, and the targeted treatment of co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Classifications of Intellectual Disability Severity. DSM-5 defines intellectual disabilities as neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in childhood and are characterized by intellectual difficulties as well as difficulties in conceptual, social, and practical areas of living. The DSM-5 diagnosis of ID requires the satisfaction of three criteria: 1.Deficits in intellectual functioning—“reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience”—confirmed by clinical evaluation and individualized standard IQ testing (APA, 2013, p. 33); 2.Deficits in adaptive functioning that significantly hamper conforming to developmental and sociocultural standards for the individual's independence and ability to meet their social responsibility; and 3.The onset of these deficits during childhood. The DSM-5 definition of ID encourages a more comprehensive view of the individual than was true under the fourth edition, DSM-IV. The DSM-IV definition included impairments of general mental abilities that affect how a person functions in conceptual, social, and daily life areas. DSM-5 abandoned specific IQ scores as a diagnostic criterion, although it retained the general notion of functioning two or more standard deviations below the general population. DSM-5 has placed more emphasis on adaptive functioning and the performance of usual life skills. In contrast to DSM-IV, which stipulated impairments in two or more skill areas, the DSM-5 criteria point to impairment in one or more superordinate skill domains (e.g., conceptual, social, practical) (Papazoglou et al., 2014). Classifications of Severity The terms “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” and “profound” have been used to describe the severity of the condition (see Table 9-1). This approach has been helpful in that aspects of mild to moderate ID differ from severe to profound ID. The DSM-5 retains this grouping with more focus on daily skills than on specific IQ range. Mild to Moderate Intellectual Disability The majority of people with ID are classified as having mild intellectual disabilities. Individuals with mild ID are slower in all areas of conceptual development and social and daily living skills. These individuals can learn practical life skills, which allows them to function in ordinary life with minimal levels of support. Individuals with moderate ID can take care of themselves, travel to familiar places in their community, and learn basic skills related to safety and health. Their self-care requires moderate support. Severe Intellectual Disability Severe ID manifests as major delays in development, and individuals often have the ability to understand speech but otherwise have limited communication skills (Sattler, 2002). Despite being able to learn simple daily routines and to engage in simple self-care, individuals with severe ID need supervision in social settings and often need family care to live in a supervised setting such as a group home. Profound Intellectual Disability Persons with profound intellectual disability often have congenital syndromes (Sattler, 2002). These individuals cannot live independently, and they require close supervision and help with self-care activities. They have very limited ability to communicate and often have physical limitations. Individuals with mild to moderate disability are less likely to have associated medical conditions than those with severe or profound ID. Formal disorders of thinking (disorders of the associative process) and the so-called pathological ideas are distinguished. Thinking disorders by form (disorders of the associative process) This rubric includes a number of violations of the way of thinking in terms of form: a change in its pace, mobility, harmony, purposefulness. Disorders of the pace of thinking Painfully accelerated thinking. It is characterized by an increase in speech production per unit of time. It is based on the acceleration of the course of the associative process. The flow of thought is determined by external associations, each of which is an impetus for a new topic of reasoning. The accelerated nature of thinking leads to superficial, hasty judgments and conclusions. Patients speak hastily, without pauses, separate parts of the phrase are connected with each other by superficial associations. Speech takes on the character of a "telegraph style" (patients skip alliances, interjections, "swallow" prepositions, prefixes, endings). “Leap of ideas” is an extreme degree of accelerated thinking. Painfully accelerated thinking is observed in manic syndrome, euphoric states. Painfully slow thinking. In terms of pace, it is the opposite of the previous disorder. Often combined with hypodynamia, hypothymia, hypomnesia. It is expressed in speech inhibition, stuckness. Associations are poor, switchability is difficult. Patients in their thinking are not able to cover a wide range of issues. Few inferences are difficult to form. Patients rarely show speech activity spontaneously, their answers are usually laconic, monosyllabic. Sometimes contact cannot be established at all. This disorder is observed in depression of any origin, with traumatic brain damage, organic, infectious diseases, epilepsy. Disorders of harmony of thinking Broken thinking is characterized by the absence of logical agreements between words in the speech of patients, while grammatical connections can be preserved. Nevertheless, the patient's speech may be completely incomprehensible, devoid of any meaning, for example: "Who can single out the temporary discrepancy in the rela tivity of concepts included in the structure of the world", etc. With incoherent thinking, not only logical, but also grammatical connections between words are absent. The speech of the patients turns into a set of separate words or even sounds: "I'll take it ... I'll get it myself ... day-stump ... ah-ha-ha ... laziness" and so on. This disorder of thinking occurs in schizophrenia, exogenous organic psychoses, accompanied by amentive clouding of consciousness. Violation of purposefulness of thinking Reasoning (fruitless philosophizing, reasoning). Thinking with a predominance of lengthy, abstract, vague, often insignificant reasoning on general topics, about well-known truths, for example, to the doctor's question "how do you feel?" They talk for a long time about the benefits of nutrition, rest, vitamins. This type of thinking is most common in schizophrenia. Autistic thinking (from the word autos - self) is thinking divorced from reality, contradicting reality, not corresponding to reality and not being corrected by reality. Patients lose touch with reality, plunge into the world of their own bizarre experiences, ideas, fantasies, incomprehensible to others. Autistic thinking refers to the main symptoms of schizophrenia, but it can also occur in other diseases and pathological conditions: schizoid psychopathy, schizotypal disorders. Symbolic thinking. Thinking, in which ordinary, commonly used words are given a special, abstract meaning, understandable only to the patient himself. In this case, words and concepts are often replaced by symbols or new words (neologisms), patients develop their own language systems. Examples of neologisms: "mirrorlastr, pincenecho, electric excursion". This kind of thinking occurs in schizophrenia. Pathological thoroughness (detail, viscosity, inertia, stiffness, torpid thinking). It is characterized by a tendency to detail, getting stuck in particulars, "marking time", inability to separate the main from the secondary, the essential from the nonessential. The transition from one circle of representations to another (switching) is difficult. It is very difficult to interrupt the speech of patients and direct them in the right direction. This type of thinking is most often found in patients with epilepsy, with organic diseases of the brain. Perseveration of thinking. It is characterized by the repetition of the same words, phrases, due to the pronounced difficulty in the switchability of the associative process and the dominance of any one thought, representation. This disorder is found in epilepsy, organic diseases of the brain, in depressed patients. Thought disorders by content Includes delusional, overvalued, and obsessive ideas. Delusional ideas. They are false, erroneous judgments (conclusions) that have arisen on a painful basis and are inaccessible to criticism and correction. Sooner or later, a deluded, but healthy person can either be dissuaded, or he himself will understand the erroneousness of his views. Delirium, being one of the manifestations of mental disorder in general, can be eliminated only through special treatment. According to psychopathological mechanisms, delusional ideas are divided into primary and secondary. Primary delirium, or delusion of interpretation, interpretation arises directly from disorders of thinking and comes down to the establishment of wrong connections, misunderstanding of the relationship between real objects. Perception is usually not affected here. In isolation, primary delusional ideas are observed in relatively mild mental illness. The painful basis here is most often a pathological character or personality changes. Secondary, or sensory delirium is a derivative of other primary psychopathological disorders (perception, memory, emotion, consciousness). There are hallucinatory, manic, depressive, confabulatory, figurative delusions. From what has been said, it follows that secondary delusions arise at a deeper level of mental disorders. This level or "register", as well as genetically related delusions, is called paranoid (as opposed to the primary paranoid). In terms of content (on the topic of delirium), all delusional ideas can be divided into three main groups: persecution, greatness and self-deprecation. The group of ideas of persecution includes delusions of poisoning, relationships, exposure, persecution itself, "love charm". Delusional ideas of greatness are also varied in content: delusions of invention, reformism, wealth, high origin, delusions of greatness. The delusional ideas of self-abasement (depressive delirium) include delusions of self-accusation, selfabasement, sinfulness, guilt. Depressive plots are usually accompanied by depression and asthenic presentation. Paranoid delusions can be both asthenic and stenic ("persecuted persecutor"). Delusional syndromes Paranoia syndrome is characterized by systematized delusions of attitude, jealousy, and invention. Judgments and conclusions of patients outwardly give the impression of quite logical, but they proceed from the wrong premises and lead to wrong conclusions. This delusion is closely related to the life situation, the personality of the patient, either altered by a mental illness, or pathological from birth. Hallucinations are usually absent. The behavior of patients with paranoid delusions is characterized by litigation, querulant tendencies, and sometimes aggressiveness. Most often this syndrome is observed in alcoholic, presenile psychoses, as well as in schizophrenia and psychopathies. Paranoid Syndrome. It is characterized by secondary delusions. The group of paranoid syndromes includes hallucinatory-delusional, depressive-delusional, catatonic-delusional and some other syndromes. Paranoid syndromes occur in both exogenous and endogenous psychoses. In schizophrenia, one of the most typical variants of the hallucinatory-paranoid syndrome is often observed - the Kandinsky-Clerambo syndrome, which consists of the following symptoms: pseudohallucinations, mental automatisms, delusional ideas of influence. Automatism is the phenomenon of loss of a sense of belonging to oneself of thoughts, emotional experiences, actions. For this reason, the mental actions of patients are subjectively perceived as automatic. G. Clerambault (1920) described three types of automatisms: 1. Ideatorial (associative) automatism manifests itself in a feeling of post-emotional interference in the course of thoughts, their insertion or withdrawal, breaks (sperrungs) or influxes (mentism), the feeling that the patient's thoughts become known to others (a symptom of openness), "echo of thoughts", violent internal speech, verbal pseudo-hallucinations, perceived as a sensation of transmission of thoughts over a distance. 2. Sensory (senestopathic, sensual) automatism. It is characterized by the perception of various unpleasant sensations in the body (senestopathy), a burning sensation, twisting, pain, sexual arousal as made, specially caused. Taste and olfactory pseudo-hallucinations can be considered as variants of this automatism. 3. Motor (kinesthetic, motor) automatism is manifested by the feeling of the compulsion of certain actions, actions of the patient, which are performed against his will or caused by external influences. At the same time, patients often experience a painful feeling of physical lack of freedom, calling themselves "robots, phantoms, puppets, automata", etc. (feeling of mastery). Explaining such internal experiences with the help of hypnosis, cosmic rays or various technical means is called delusion of influence and sometimes has a rather ridiculous (autistic) character. At the same time, affective disorders are most often represented by a feeling of anxiety, tension, in acute cases - the fear of death. Paraphrenic syndrome. It is characterized by a combination of fantastic, ridiculous ideas of greatness with expansive affect, phenomena of mental automatism, delusions of influence and pseudo-hallucinations. Sometimes the delusional statements of patients are based on fantastic, fictional memories (confabulatory delirium). In paranoid schizophrenia, paraphrenic syndrome is the final stage in the course of psychosis. In addition to the chronic delusional syndromes described above, in clinical practice, there are acutely developing delusional states that have a better prognosis (acute paranoia, acute paranoid, acute paraphrenia). They are characterized by the severity of emotional disorders, a low degree of systematization of delusional ideas, dynamism of the clinical picture and correspond to the concept of acute sensory delirium. At the height of these states, signs of gross disorganization of mental activity as a whole can be observed, including signs of impaired consciousness (oneiroid syndrome). Acute sensory delirium can also be represented by the Capgras syndrome (Capgras J., 1923), which includes, in addition to anxiety and ideas of staging, the symptom of doubles. With the symptom of a negative double, the patient claims that a loved one, for example, a mother or father, is not such, but is a dummy figure, disguised as his parents. The symptom of a positive double is the belief that unfamiliar persons, who deliberately changed their appearance, appear to the patient as close people. Cotard's syndrome (nihilistic delirium, delusion of denial), (Cotard J., 1880) is expressed in erroneous conclusions of a megalomaniac, hypochondriacal nature about one's health. Patients are convinced that they have a serious, fatal disease (syphilis, cancer), "inflammation of all the viscera", they speak of damage to certain organs or parts of the body ("the heart stopped working, blood clotted, the intestines rotted, food is not processed and comes from the stomach through lungs to the brain ", etc.). Sometimes they claim that they died, turned into a rotting corpse, died. Overvalued ideas Overvalued ideas are judgments arising on the basis of real facts, which are emotionally overestimated, hyperbolized and occupy an unreasonably large place in the minds of patients, displacing competing ideas. Thus, at the height of this process, with overvalued ideas, as well as with delirium, criticism disappears, which makes it possible to classify them as pathological. Inferences arise both on the basis of the logical processing of concepts, representations (rationally), and with the participation of emotions, organizing and directing not only the thinking process itself, but evaluating its result. For personalities of the artistic type, the latter can be of decisive importance according to the principle: "if you cannot, but you really want to, then you can." The balanced interaction of the rational and emotional components is called affective coordination of thinking. Emotional disorders observed in various diseases and anomalies cause its disturbances. Overvalued ideas are a special case of inadequately excessive saturation of affect with any particular group of ideas, depriving all others of the competitiveness. This psychopathological mechanism is called the catatimy mechanism. It is quite understandable that pathological ideas arising in this way can have not only personal, painful, situational conditioning, but also substantively related to life topics that cause the greatest emotional resonance. These topics are most often love and jealousy, the significance of one's own activities and the attitude of others, one's own well-being, health and the threat of losing both. Most often, overvalued ideas arise in situations of conflict in psychopathic personalities, in the debut manifestations of exogenous organic and endogenous diseases, as well as in cases of their mild course. In the absence of persistent disorganization of the emotional background, they can have a transient character and, when ordering it, be accompanied by a critical attitude. Stabilization of affective disorders during the development of mental illness or chronicity of the conflict in abnormal individuals leads to a persistent decrease in critical attitude, which some authors (A.B.Smulevich) propose to call "overvalued delirium." Obsessions Obsessions, or obsessions, are spontaneously obsessive pathological ideas that are always critical. Subjectively, they are perceived as painful and in this sense are "foreign bodies" of mental life. Most often, obsessive thoughts are observed in diseases of the neurotic circle, however, they can also occur in practically healthy people with an anxious and suspicious character, rigidity of mental processes. In these cases, they tend to be unstable and not cause significant concern. In case of mental illness, on the contrary, concentrating on oneself and on the struggle with them all the activity of the patient is experienced as extremely painful and painful. Depending on the degree of emotional saturation, firstly, abstract (abstract) obsessions are distinguished. They can be represented by obsessive philosophizing ("mental chewing gum"), obsessive counting (arithmania). Emotionally intense obsessions include obsessive doubts and contrasting obsessions. With them, patients can repeatedly return home, experiencing anxious doubts whether they closed the door, turned off the gas, iron, etc. At the same time, they perfectly understand the absurdity of their experiences, but they are unable to overcome the doubts that arise again and again. With contrasting obsessions, patients are gripped by the fear of doing something unacceptable, immoral, illegal. Despite all the painfulness of these experiences, patients never try to realize the impulses that have arisen. Obsessions tend to be the ideational component of obsessions and are rarely found in their pure form. Their structure also has an emotional component (obsessive fears - phobias), obsessive drives - compulsions, motor disorders - obsessive actions, rituals. In the most complete form, these disorders are presented in the framework of the obsessive-phobic syndrome. Obsessive fears (phobias) can have different content. In neuroses, they are most often understandable, closely related to the patient's real life situation: fears of pollution and infection (misophobia), closed rooms (claustrophobia), crowds and open spaces (agoraphobia), death (thanatophobia). Most often there are obsessive fears of a serious illness (nosophobia), especially in cases provoked psychogenically: cardiophobia, carcinophobia, syphilophobia, speed phobia. In schizophrenia, obsessive experiences often have an absurd, incomprehensible, disconnected from life content - for example, thoughts that cadaveric poison, needles, pins may be present in the food consumed; domestic insects can crawl into the ear, nose, brain, etc. Anxiously tense affect in these cases is quite often weakened by rituals - a kind of symbolic protective actions, the absurdity of which patients can also understand, but their implementation brings relief to patients. For example, to distract themselves from obsessive thoughts of infection, patients wash their hands a certain number of times, using soap of a certain color. To suppress claustrophobic thoughts, before entering the elevator, they turn around three times on their axis. Patients are forced to repeat such actions many times with all the understanding of their meaninglessness. Most often, obsessive-phobic syndrome is observed in obsessive-compulsive disorder. It can also occur within the framework of endogenous psychoses, for example, with neurosis-like debuts in schizophrenia, as well as with constitutional anomalies (psychasthenia). One of the variants of obsessive-phobic syndrome is dysmorphophobic (dysmorphomanic) syndrome. In this case, the patient's experiences are focused on the presence of either an imaginary or a real physical handicap or deformity. They can be both in the nature of obsessive fears and overvalued thoughts with a decrease or absence of critical attitude, intense affect, secondary ideas of attitude, and improper behavior. In these cases, patients try to eliminate the existing shortcomings on their own, for example, get rid of freckles with acid, fight excessive obesity, resorting to exhausting fasting, or turn to specialists in order to surgically eliminate the deformity that they believe exists. Dysmorphomania syndrome can be observed in abnormal personalities in adolescence and adolescence, more often in girls. Also, they often have syndromes close to this - anorexia nervosa syndrome and hypochondriacal syndrome. The delusional variant of the syndrome of dysmofomania is most typical for the onset manifestations of paranoid schizophrenia. What are the types of delusional disorder? There are different types of delusional disorder based on the main theme of the delusions experienced. The types of delusional disorder include: Erotomanic. Someone with this type of delusional disorder believes that another person, often someone important or famous, is in love with him or her. The person might attempt to contact the object of the delusion, and stalking behavior is not uncommon. Grandiose. A person with this type of delusional disorder has an over-inflated sense of worth, power, knowledge, or identity. The person might believe he or she has a great talent or has made an important discovery. Jealous. A person with this type of delusional disorder believes that his or her spouse or sexual partner is unfaithful. Persecutory. People with this type of delusional disorder believe that they (or someone close to them) are being mistreated, or that someone is spying on them or planning to harm them. It is not uncommon for people with this type of delusional disorder to make repeated complaints to legal authorities. Somatic. A person with this type of delusional disorder believes that he or she has a physical defect or medical problem. Mixed. People with this type of delusional disorder have two or more of the types of delusions listed above.