РАЗВИТИЕ ГРАММАТИКИ В СРЕДНЕ

advertisement

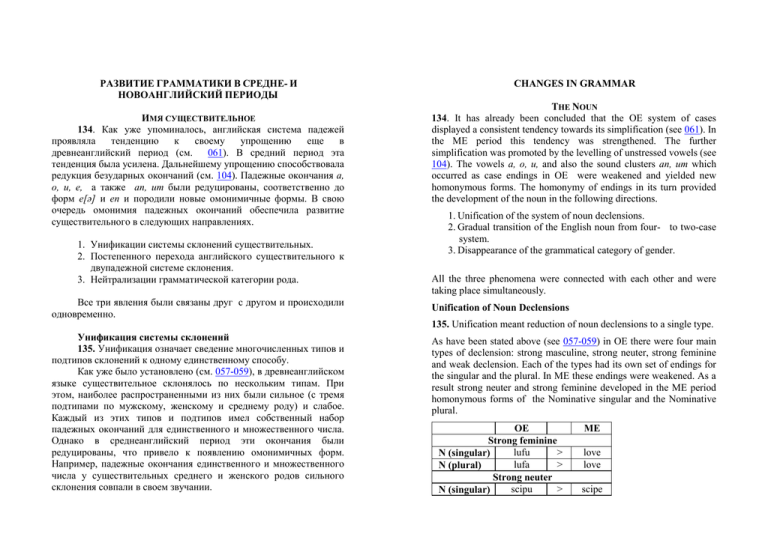

РАЗВИТИЕ ГРАММАТИКИ В СРЕДНЕ- И НОВОАНГЛИЙСКИЙ ПЕРИОДЫ ИМЯ СУЩЕСТВИТЕЛЬНОЕ 134. Как уже упоминалось, английская система падежей проявляла тенденцию к своему упрощению еще в древнеанглийский период (см. 061). В средний период эта тенденция была усилена. Дальнейшему упрощению способствовала редукция безударных окончаний (см. 104). Падежные окончания a, o, u, e, а также an, um были редуцированы, соответственно до форм e[ə] и en и породили новые омонимичные формы. В свою очередь омонимия падежных окончаний обеспечила развитие существительного в следующих направлениях. 1. Унификации системы склонений существительных. 2. Постепенного перехода английского существительного к двупадежной системе склонения. 3. Нейтрализации грамматической категории рода. Все три явления были связаны друг с другом и происходили одновременно. CHANGES IN GRAMMAR THE NOUN 134. It has already been concluded that the OE system of cases displayed a consistent tendency towards its simplification (see 061). In the ME period this tendency was strengthened. The further simplification was promoted by the levelling of unstressed vowels (see 104). The vowels a, o, u, and also the sound clusters an, um which occurred as case endings in OE were weakened and yielded new homonymous forms. The homonymy of endings in its turn provided the development of the noun in the following directions. 1. Unification of the system of noun declensions. 2. Gradual transition of the English noun from four- to two-case system. 3. Disappearance of the grammatical category of gender. All the three phenomena were connected with each other and were taking place simultaneously. Unification of Noun Declensions 135. Unification meant reduction of noun declensions to a single type. Унификация системы склонений 135. Унификация означает сведение многочисленных типов и подтипов склонений к одному единственному способу. Как уже было установлено (см. 057-059), в древнеанглийском языке существительное склонялось по нескольким типам. При этом, наиболее распространенными из них были сильное (с тремя подтипами по мужскому, женскому и среднему роду) и слабое. Каждый из этих типов и подтипов имел собственный набор падежных окончаний для единственного и множественного числа. Однако в среднеанглийский период эти окончания были редуцированы, что привело к появлению омонимичных форм. Например, падежные окончания единственного и множественного числа у существительных среднего и женского родов сильного склонения совпали в своем звучании. As have been stated above (see 057-059) in OE there were four main types of declension: strong masculine, strong neuter, strong feminine and weak declension. Each of the types had its own set of endings for the singular and the plural. In ME these endings were weakened. As a result strong neuter and strong feminine developed in the ME period homonymous forms of the Nominative singular and the Nominative plural. OE Strong feminine lufu > N (singular) lufa > N (plural) Strong neuter scipu > N (singular) ME love love scipe N (plural) OE Сильное склонение, ж.р. lufu > И.п., ед.ч. lufa > И.п., мн.ч. Сильное склонение, с.р. scipu > И.п., ед.ч. scipa > И.п., мн.ч. scipa > scipe ME love love scipe scipe Чтобы устранить это неудобство, язык стал подыскивать для этих существительных новые формы разграничения числа. Существительные среднего рода стали строить формы множественного числа по аналогии с существительными мужского рода сильного склонения, т.е. при помощи окончания es; существительные женского рода стали тяготеть к слабому склонению существительных, имевших в окончании множественного числа en. Примечание: Закон аналогии проявляется в способности больших групп языковых единиц поглощать малые группы, заставляя их изменять формы по своим собственным моделям. Например, русское слово «опенок» сменило форму множественного числа «опенки» на форму «опята», следуя модели «котенок котята», «ягненок - ягнята», «теленок - телята» и т.д. Закон аналогии не обошел и прочие типы склонения, приводя множественное число всех существительных либо к окончанию -es (сильное склонение), либо к окончанию -en (слабое склонение). Таким образом к концу XII века в системе склонений существительного остались лишь два типа: сильное и слабое. Между тем существительные с окончанием -es во множественном числе оказались более многочисленными, и это окончание понималось носителями языка как главное средство выражения множественности. К концу XIV века это окончание стали принимать (за небольшим исключением) все существительные английского языка. Таким образом система склонений английского существительного была приведена к одному единственному типу. This proved to be rather inconvenient for the process of communication. That is why in accordance with the law of analogy these types of declension rearranged their case forms after the patterns of other types of declension. Feminine nouns took in the plural the ending -en, by analogy with weak declension, neuter nouns were inflected by -es, like strong masculine nouns. Note: The law (action) of analogy in language means that larger groups of language units absorb smaller ones and make their members follow the patterns of absorbing group. Thus, for example, the action of analogy made the Russian word «опенок» drop its former plural form «опенки» (which preserves the root of the word) and build the form «опята» (which does not preserve the root) after the pattern «котенок котята», «ягненок - ягнята», «теленок - телята», etc. The law of analogy affected also all the minor types of declension and brought the plurals of all the nouns either to -es (strong declension), or to -en form (weak declension). Thus towards the end of the 12th century the four main types of noun declension were reduced to two types: strong with plural in -es and weak with plural in -en. However the class of nouns with plurals in -es was by far more numerous and, therefore, more influential. The affix -es came to be understood as the main affix of the plural and towards the end of the 14th century it was added to all the nouns with some rare exceptions. Thus the system of declensions was brought to one type only. The nouns that preserve old forms of the plural are well known to any learner of English. They may be grouped under the following headings. Survivals of ME weak declension: ox - oxen, brother brethren, child - children; Survivals of OE mutated plurals: foot - feet, tooth - teeth, goose - geese, mouse - mice, louse - lice, man - men, woman - women; Survivals of uninflected plurals: deer, swine, sheep. Некоторые существительные, однако, сохраняют остатки древних парадигм вплоть до настоящего времени. Эти существительные хорошо известны любому изучающему английский язык. Существительные, принимающие архаичный суффикс – en: ox - oxen, brother - brethren, child - children; Существительные, сохраняющие чередование корневого гласного: foot - feet, tooth - teeth, goose - geese, mouse mice, louse - lice, man - men, woman - women; Существительные, имеющие омонимичные формы единственного и множественного числа: deer, swine, sheep. Сокращение числа падежей 136. Еще одним явлением, способствующим упрощению системы английского существительного явился его переход к двупадежной системе склонения. Редукция безударных окончаний и их последующая утрата стерли различия между именительным, родительным и дательным падежами. И Р Д В Ед.ч. stone stones stone stone Мн.ч. stones stones stones stones Единственным окончанием, которое сохранялось в течение средне- и новоанглийского периодов, было окончание –es (родительный падеж, ед.ч. и именительный падеж мн.ч.). Это окончание было защищено согласным –s и поэтому не было утрачено. Более того оно распространилось на все падежи множественного числа. Имея одинаковые окончания, именительный, дательный и винительный слились в один падеж, называемый сегодня «общим падежом». Функции генитива сузились. К XVI веку он стал ассоциироваться главным образом со значением принадлежности, а его употребление стало ограничиваться одушевленными Reduction of Cases 136. Another phenomenon that promoted simplification of the noun system was reduction of cases. The weakening of case endings and their subsequent loss eliminated distinctions between the Nominative, Accusative and Dative. Singular N stone G stones D stone A stone Plural stones stones stones stones The only ending that survived through the centuries of the ME and NE periods was the ending -es found in the Nominative plural and Genitive singular. It was protected by the consonant -s and therefore did not vanish. More than that the ending -es spread also to all the cases of the plural. The Nominative, Dative and Accusative merged into one case which is now termed «Common». The functions of Genitive were narrowed. Towards the 16th century its meaning was mainly associated with the idea of possessiveness and it came to be used mainly with nouns denoting men or animals. The apostrophe was introduced in the 17th century. Loss of Grammatical Category of Gender 137. Simplification of the noun system was completed by the loss of gender distinctions. In OE the feeling for grammatical gender was secured by grammatical agreement of the noun with the adjective. In other words the case ending of the adjective was predetermined by the gender of the noun: sē gōda mann (this good man) - masculine; sēо gōdan cwēne (this good woman) - feminine (see also 067). In accordance with the general development the endings were weakened and lost, the adjective ceased to be inflected for gender, and the gender of the noun lost its grammatical support. существительными. Знак «апостроф» появился в XVII веке. Утрата грамматической категории рода 137. Упрощение системы существительных было завершено стиранием их различий в грамматическом роде. Род как грамматическая категория в древнеанглийском языке существовал благодаря согласованию существительного и прилагательного. Иными словами падежное окончание прилагательного предопределялось родом существительного: sē gōda mann (this good man) – м.р. sēо gōdan cwēne (this good woman) – ж.р. (см. также 067). В соответствии с общим направлением развития, окончания сначала редуцировались, а затем были утрачены. Прилагательное потеряло морфологические показатели рода, а род существительного стал терять грамматическую поддержку. M F OE sē gōda mann sēо gōdan cwēne M F OE gōd mann gōdu cwēne Слабое склонение ME that goode man that gooden queene Сильное склонение ME good man goode queene M F OE gōd mann gōdu cwēne Weak adjectives ME that goode man that gooden queene Strong adjectives ME good man goode queene NE that good man that good queen NE good man good queen THE PRONOUN Personal Pronouns 138. The development of personal pronouns in ME and NE was characterized by the following changes. NE that good man that good queen NE good man good queen МЕСТОИМЕНИЕ Личные местоимения 138. Развитие личных местоимений в средне- и новоанглийский периоды характеризовалось следующими направлениями. 1. 2. 3. 4. M F OE sē gōda mann sēо gōdan cwēne Исчезновение двойственного числа. Упрощение падежной системы. Изменение графической и звуковой формы местоимений. Вытеснение старых местоимений заимствованными формами. 1. 2. 3. 4. Disappearance of the dual number. Simplification of the case system. Modification of the graphic and sound form of pronouns. Replacement of pronouns. 139. The personal pronoun was the only part of speech in OE that had the dual number (see 063). Neither the verb nor the noun made these distinctions. So if used as the subject the pronoun in the dual number could not find grammatical support of the predicate (expressed by a verb). The verb in such cases was used in its plural form as denoting the idea «more than one». Thus, it was only natural that the dual of the pronoun was lost, and its functions were taken by the plural. Towards the end of the 12th century the dual pronouns fell in disuse. 140. In ME the case system of personal pronouns underwent simplification which was the result of the following phenomena. The Dative and the Accusative fused into one case which is now called the Objective case. This process began in OE. It has been mentioned (see 063) that the Accusative of OE personal pronouns (the 1st and the 2nd persons) had two parallel forms. One of them was 139. Древнеанглийское личное местоимение было единственной частью речи, которая имела двойственное число (см. 063). Этой формы не было ни у глагола, ни у существительного. Поэтому, функционируя в качестве подлежащего, двойственное число местоимений не находило грамматической поддержки у сказуемого. Глагол в таких случаях использовался во множественном числе, выражая значение «более, чем один». Совершенно естественно поэтому, что формы двойственного числа местоимения были утрачены, а их функции были приняты формами множественного числа. К концу XII века формы двойственного числа полностью вышли из употребления. 140. В среднеанглийский период падежная система личных местоимений претерпевала изменения, которые стали следствием следующих явлений. Как уже упоминалось (см. 063) винительный падеж древнеанглийского личного местоимения (первое и второе лицо) имел две параллельные формы, причем одна из них совпадала с формой дательного падежа. Именно эта форма была наиболее частотной, что заставляло дательный и винительный падежи первого и второго лица сливаться в один (который сегодня называется объектным). В среднеанглийский период это явление распространилось и на третье лицо. Таким образом, различия между дательным и винительным падежами всех форм личных местоимений были сведены к нулю. Родительный падеж личных местоимений стал развиваться как местоимение особого типа. Еще в древнеанглийский период формы генитива первого и второго лица получили собственную систему склонения, схожую с системой склонения прилагательных. По сути дела это означало появление нового типа местоимений. В среднеанглийский период эти формы утратили все функции кроме одной (обозначения принадлежности), и утвердились в языке как класс притяжательных местоимений. Таким образом, к XIV веку система личных местоимений сохранила за собой лишь два падежа: общий и объектный, которые сохраняются и в языке современности. 141. Подчиняясь законам языкового развития, все личные identical to the form of the Dative. It is this form that was most frequently used, and practically OE pronouns of the first and the second persons did not differentiate between the Dative and the Accusative. In ME this process was completed. The pronouns of the third person also ceased to make distinctions between the Accusative and the Dative. The Genitive case developed into an independent type of pronoun. This process also began as early as in the OE period. Towards the 9th century the Genitive forms of the first and the second person acquired their own system declension (they came to be declined like adjectives). This meant the rise of a new independent type of pronouns. In ME these forms lost all their functions except indicating possession, and established themselves as the class of possessive pronouns. Thus, towards the 14th century the system of the personal pronoun had two cases: Common and Objective. These two cases are preserved in the language of today. 141. All personal pronouns modified their graphic and sound form in accordance with the phonetic phenomena occurring in ME and NE. The pronoun I originated from OE ic. In ME due to the palatalization (see 041), [k] in ic changed into [t∫]: ic > ich. In early NE [t∫] lost and [i] was lengthened, ich > i[i:]. In later years long [i:] was subject to the Great Vowel Shift (see 108) and changed into [ai]: i[i:] > I [ai]. The Great Vowel shift also affected the vowel [e:] in the forms wē, mē , hē . In accordance with this phenomenon [e:] changed into [i:]. OE hit lost the initial [h] and developed into NE it. Modern you developed from OE ēow, the Dative form of gē. 142. Several OE pronouns did not survive. They were either lost (as the duals, for example), or replaced by other pronouns. Thus, the modern pronoun they was borrowed from Scandinavian. It replaced the OE pronoun hīe. Modern she is supposed to have originated from the feminine demonstrative sēo. This pronoun replaced OE hēo. Most местоимения модифицировали свое звучание и графическую форму. Современное местоимение I исходит из древнеанглийского ic. В силу палатализации (см. 041), [k] в местоимении ic превратился в [t∫]: ic > ich. В ранненовоанглийский период [t∫] был утрачен, а гласный [i] удлинился: ich > i[i:]. В последующие годы долгий [i:] подвергался великому сдвигу гласных (см. 108) и дифтонгизировался в [ai]: i[i:] > I [ai]. Великий сдвиг гласных повлиял и на гласный [e:] в местоимениях wē, mē , hē. В соответствии с этим явлением долгий [e:] изменился в [i:]. Древнеанглийское hit утратило начальный [h] и развилось в современное it. Современное you развивалось из древнеанглийского ēow, дательного падежа местоимения gē. 142. Некоторые древнеанглийские местоимения не сохраняются в языке современности. Одни из них (например, формы двойственного числа) были утрачены. Другие вытеснялись заимствованиями или другими местоимениями. Например, современное they было заимствовано из языка скандинавов. Оно заменило древнеанглийское местоимение hīe. Современное she, как считается, исходит из указательного местоимения женского рода sēo, которое стало использоваться вместо древнеанглийского hēo. Вероятнее всего обе замены были вызваны омонимией. В быстрой речи древнеанглийские hē (he), hēo (she) и hīe (they) были неразличимыми. Примечание: Существует также предположение, что современное she развивалось из скандинавского личного местоимения scæ. В конце среднеанглийского периода местоимение you (второе лицо множественное число) стало использоваться вместо thou < OE þū (второе лицо, единственное число); сначала в вежливых обращениях, затем и во всех других случаях. Сегодня форма thou используется в языке поэзии и религии. Указательные местоимения probably these two replacements were caused by homonymy. In rapid speech OE hē (he), hēo (she) и hīe (they) sounded very much alike, or were just indistinguishable. Note: There is also a point of view according to which ME she developed from the Scandinavian personal pronoun scæ. One more replacement was made by the plural of the second person you. It replaced the singular pronoun thou < OE þū, first in polite address, then in all the other cases. Today thou is used in the language of poetry, or religion. Demonstrative Pronouns 143. Unlike the personal pronoun which retained its case system (though in a modified form), the demonstratives did not preserve a single of its oblique cases. The only distinctions that are still made by the English demonstratives are number distinctions: that - those; this these. That is evidently the descendant of the OE þæt. As for those, its origin is debatable: it could have resulted from the development of the plural form þā (OE þā > ME tho > NE those), where -s appeared by analogy with the plurals of nouns; it could also have developed from the OE plural form þās (OE þās > ME those > NE those). The pronoun this developed from the OE neuter þis; these could have originated from the OE feminine pronoun þēos. Note: The replacement of plural forms with corresponding forms of the feminine gender is highly probable because in different Indo-European languages these forms often sound alike. Cf., for instance, German sie (she) and sie (they), Old English hire (her) and hira (their), Russian борода and города. THE ADJECTIVE 144. As well as the English noun the English adjective developed towards its simplification. And as well as the development of the noun the development of the adjective was caused by the general tendency towards reduction of case endings. However, unlike the noun the adjective lost all its distinctions in number, case and gender. The only inflections that were retained were the inflections of comparison. 143. В ходе своего развития в средне- и новоанглийский периоды указательное местоимение претерпело значительные изменения. Была полностью разрушена его падежная система, а единственные различия, сохранившиеся до настоящего состояния языка – это различия в числе: that - those; this - these. That, вероятно, исходит из древнеанглийского þæt. Происхождение местоимения those, дискуссионно. Ученые рассматривают два источника его появления. Оно могло стать результатом развития множественной формы þā (OE þā > ME tho > NE those), где окончание -s появилось по аналогии с множественным числом существительных. Оно также могло развиваться из множественной формы þās (OE þās > ME those > NE those). Местоимение this развивалось из древнеанглийского местоимения среднего рода þis; форма множественного числа these, скорее всего, появилась как результат эволюции древнеанглийского местоимения женского рода þēos. Примечание: Замена форм множественного числа формами женского рода вполне возможна, поскольку многие индоевропейские языки демонстрируют в этих категориях звуковое сходство. Ср., напр., немецкие sie (she) и sie (they), древнеанглийские hire (her) и hira (their), русские борода и города. ИМЯ ПРИЛАГАТЕЛЬНОЕ 144. Прилагательное, как и другие части речи эволюционировало в средне- и новоанглийский периоды в сторону упрощения своей системы. В результате редукции и последующей утраты безударных окончаний английское прилагательное растеряло все свои грамматические категории за исключением категории сравнения. 145. Суффикс сравнительной степени -ra приобрел в среднеанглийский период форму -re, а в новоанглийский период изменился в -er. Древнеанглийский суффикс -ost редуцировался до -est. glædra glædost OE glæd gladre gladdest ME glad 145. The suffix of the comparative degree -ra was reduced to -re in ME and in NE it changed into -er. The OE suffix -ost changed into est. OE ME NE glæd glad glad glædra gladre gladder glædost gladdest gladdest Many of the OE mutated forms retained the vowel interchange in ME, but lost all signs of mutation in NE, e.g.: OE ME NE strong strong strong strengra strengre stronger strengost strengest strongest However two of such adjectives still retain the mutated vowel in the comparative and the superlative degrees: old (elder, eldest); far (further, furthest). The suppletive forms also survived throughout the history, but the word yfel (evil) was replaced by the word bad. good bad much/many little better worse more less best worst most least Towards the 15 century the English adjective began to build degrees of comparison analytically, i.e. with the help of auxiliary words more and most: paynfull strong hard more paynfull more strong more hard most paynfull most strong most hard In NE these patterns became very frequent. They could be applied to any adjective irrespective of its morphological structure. In due course, however the analytical way was restricted to polysyllabic adjectives only. NE glad gladder gladdest Древнеанглийские прилагательные, подвергавшиеся переднеязычной перегласовке в корне, сохраняли ее свидетельства в среднеанглийском периоде, но утратили эти свидетельства в ходе дальнейшего развития. OE ME NE strong strong strong strengra strengre stronger strengost strengest strongest Между тем два английских прилагательных донесли свидетельства палатальной перегласовки вплоть до современного состояния языка: old (elder, eldest); far (further, furthest). Система прилагательного сохранила и суплетивные степени сравнения, однако на место древнеанглийского yfel (evil) пришло прилагательное bad. good bad much/many little better worse more less best worst most least К началу XV века английское прилагательное начало строить степени сравнения аналитическим путем, т.е. при помощи вспомогательных слов more и most: paynfull strong hard more paynfull more strong more hard most paynfull most strong most hard В новоанглийский период эти формы стали использоваться регулярно. Сначала они служили для построения степеней сравнения любых прилагательных. С течением времени, однако, их употребление стало ограничиваться лишь многосложными прилагательными. THE VERB 146. The development of the verb in ME and NE was marked by two contradictory tendencies. On the one hand the verb system got simplified, on the other hand it became more complicated. Simplification affected synthetic means of building verb forms. As a result the English verb lost its person and number distinctions in many positions. Alongside this the system of the English verb gained its complexity by developing new categorial forms and new categories. These new forms and categories came to be expressed analytically. The Development of Verbal Categories 147. Person and Number. The OE verb had a rather developed system of personal endings. They made distinctions between the forms of the verbs in the present and the past, in the indicative and the subjunctive. However nearly all of them died out in the course of history and the modern English verb displays only one survival of the OE personal endings. This is the ending -es/s which exists in a few graphic and phonetic variations (he works; he writes; he teaches; he understands). The ending -es/-s developed from the inflection -eþ (þone cymeþ sē mann - then comes that man) which survived throughout the ME period (he cometh). First -eth changed into -es in the Northern dialects, and within the 15th - 16th centuries it gradually came into use in the Midland and Southern dialects. In the works by Shakespeare eth and -es appear as alternatives; in the 17th century -es became a standard; the use of –eth was restricted to certain styles. Today -eth is retained in the poetic style. The language of poetry also preserves the OE ending of the second person singular -st (thou dost; thou hast). The modern number distinctions between was and were developed from the OE opposition wæs – wæron. 148. Tense (Rise of the Future Forms). As has already been mentioned the category of tense in OE was made up of two forms: the present and the past (see 070). The future forms appeared only in ME. ГЛАГОЛ 146. Развитие глагола в средне- и новоанглийском периодах отмечается двумя противоречивыми тенденциями: тенденцией к упрощению и тенденцией к усложнению. Упрощение затронуло синтетическую сторону глагольной системы. В результате редукции безударных окончаний английский глагол утратил морфологические показатели числа и лица во многих позициях. Вместе с тем система английского глагола постепенно усложнялась, приобретая новые категориальные формы и новые грамматические категории. При этом новые формы и категории тяготели к аналитическим способам выражения. Развитие глагольных категорий 147. Лицо и число. Древнеанглийский глагол имел развитую систему личных окончаний. При этом личные формы глагола отличались друг от друга как внутри категории времени (настоящее, прошедшее), так и внутри категории наклонения (изъявительное, сослагательное). Однако в течение средне- и новоанглийского периодов различия между личными формами глагола были нейтрализованы, а до современного состояния языка дошло лишь одно из личных окончаний, т.е. окончание -es/s, существующее сегодня в трех графических и фонетических вариантах (he works; he writes; he teaches; he understands). Это окончание развивалось из древней морфемы -eþ (þone cymeþ sē mann - then comes that man), которая сохранялась и в среднеанглийский период. (he cometh). Сначала –eth изменилась в -es в северных диалектах, а в течение XV-XVI веков она стала использоваться в средних и южных диалектах. В работах Шекспира –eth и -es представлены как альтернативные варианты; в XVII веке -es становится стандартом, а использование –eth ограничивается лишь некоторыми стилями. В современном языке eth является свидетельством поэтического стиля, который также сохраняет и старое окончание второго лица единственного числа -st They originated from the OE patterns sculan + Infinitive and willan + Infinitive. Both patterns were free syntactical phrases. Each of their elements preserved its lexical meaning: scullan expressed a must and willan denoted a want. Ure æghwylc sceal ende gebīdan Each of us must await an end. Þy ylcan dæge þe hī hine to þæm āde beran wyllaþ, þone tadælaþ hī his fēoh On that very day when they want to take him to the fire they divide his property. In the course of history the verbs sculan and willan gradually lost their lexical meanings and became auxiliaries. The free syntactical phrases acquired the meaning of futurity and turned into the analytical forms of future shall do and will do. 149. Aspect (Rise of the Continuous Forms). The prefix ge- which in OE was used to express aspect distinctions (see 074) was lost in the ME period. As a result the English verb lost all the morphological means that could have been suggestive of the perfective or imperfective aspect. However, the language developed new aspect relations based on the opposition of non-continuous and continuous forms. The continuous forms are believed to take root from two sources. The first of them was the OE free syntactical phrase beon + Participle I hē wæs huntende he was hunting The form hē wæs huntende in this example expresses the state of the subject . One more source of continuous forms was the phrase beon + on + Verbal Noun in - ing hē wæs on huntinge (thou dost; thou hast). Современные формы was и were, демонстрирующие различия в числе развивались из древнеанглийской оппозиции wæs – wæron. 148. Время (Развитие форм будущего). Как уже упоминалось, категория времени в древнеанглийском языке выражалась двучленной оппозицией настоящее – прошедшее (см. 070). Формы будущего времени появились только в среднеанглийский период. Они исходили из древнеанглийских моделей sculan + Infinitive и willan + Infinitive. Обе модели были свободными синтаксическими сочетаниями, в которых каждый из составляющих сохранял свое лексическое значение: глагол scullan выражал долженствование, а willan – желание. Ure æghwylc sceal ende gebīdan Each of us must await an end. Þy ylcan dæge þe hī hine to þæm āde beran wyllaþ, þone tadælaþ hī his fēoh On that very day when they want to take him to the fire they divide his property. С течением времени глаголы sculan и willan утратили лексические значения и стали выполнять функции вспомогательных слов, а свободные синтаксические сочетания превратились в аналитические формы будущего времени shall do и will do. 149. Вид (Развитие длительных форм). С редукцией префикса ge- глагольная система утратила значительную часть средств, использовавшихся для выражения видовых значений, т.е. значений совершенности и несовершенности глагольного действия (см. 074). Однако в ходе своей эволюции язык развивал новые видовые отношения, которые имели в своей основе оппозицию длительных и недлительных форм. Считается, что длительные формы английского глагола формировались на основе взаимодействия двух источников. he was at hunt Both phrases denoted the same idea, and in the course of history they merged into one. The preposition -on was first reduced (he was ahunting) and then disappeared (he was hunting). On the other hand the verbal noun (hunting) found in this phrase came to be understood as participle and in accordance with the law of analogy all the participles gradually began to take the ending -ing. The phrase he is hunting was used to denote an action taking place continuously and at a definite time. In due course is hunting turned into the analytical form of the verb with the function of showing aspect distinctions as compared with the synthetic form hunts. 150. Mood. The evolution of mood in the ME and NE periods was remarkable for the growth of analytical units which developed into the forms of modern oblique moods. These forms emerged from free syntactical phrases wolde (would) + Infinitive and sceolde (should) + Infinitive. With the growth of perfect forms the verbs would and should came to be used with the perfect infinitive. In addition the analytical forms of the oblique moods were replenished by the forms had + Infinitive. In the course of their development the new analytical forms ousted the old synthetic ones from many of their positions. The survivals of the OE synthetic forms of the subjunctive in the English language of today are only two. They are the form homonymous with the infinitive (as in: I suggest that he do/be /take/etc.) and the form homonymous with the past (as in: I wish he did/were /took/etc.). The first of them developed from the present subjunctive, the second, from the past subjunctive. OE (Subjunctive) dō Present Singular dōn Present Plural dyde Past Singular dyden Past Plural > > > > do do did did NE (Subjunctive) Subjunctive I Subjunctive I Subjunctive II Subjunctive II Первым из этих источников является синтаксическая модель beon + Participle I. hē wæs huntende he was hunting Форма hē wæs huntende в данном примере является свободным синтаксическим сочетанием и выражает состояние субъекта (букв. Он был охотящийся). Другим источником длительных форм является сочетание beon + on + Verbal Noun на ing. hē wæs on huntinge he was at hunt (букв. Он был на охоте) Будучи синонимичными, подобные образования постепенно сливались в одно. Предлог -on редуцировался: сначала до элемента a- (he was a-hunting), а затем до нуля (he was hunting). С другой стороны, отглагольное существительное (hunting) стало пониматься как причастие, а суффикс этого существительного -ing постепенно вытеснил исконный суффикс причастия –ende. Оборот he is hunting использовался для обозначения длительного действия и с течением времени превратился в аналитическую форму глагола, противопоставленную синтетической форме hunts по видовому признаку длительное – недлительное действие. 150. Наклонение. Развитие категории наклонения в среднеи новоанглийский периоды также отмечено тенденцией к переходу на аналитические формы выражения. Источниками этих форм послужили синтаксические модели wolde (would) + Infinitive и sceolde (should) + Infinitive. С развитием форм перфекта глаголы would and should стали употребляться с перфектным инфинитивом, еще более усложняя систему английских наклонений. Кроме этого аналитические средства категории наклонения были пополнены формой had + Infinitive. В ходе своего развития аналитические формы постепенно отвоевывали позиции у старых синтетических The chart shows that the OE subjunctive made number distinctions which were neutralized with the loss of unstressed endings. 151. Voice (Rise of the Passive Forms). As have already been mentioned (see 075) the idea of passivity in OE was conveyed with the help of two syntactical phrases: weorþan (become)+ Participle II and bēon (be)+ Participle II. In ME the first of these phrases came in disuse because the verb weorþan disappeared from the language. The second of the two phrases gradually developed into the analytical form be done. In ME and further on in NE the passive of the verb acquired its perfect and continuous forms and widened the sphere of its usage. 152. Time Correlation (Rise of the Perfect Forms). As well as all the other analytical forms of the verb the perfect forms originated from OE free syntactical phrases. The patterns which gave rise to the perfect forms were two: habban (have) + Participle II and bēon (be)+ Participle II. Hæfde sē cyning his fierd on tū tonumen The king divided his army into two (parts) Þa wæron cumene of Hibernia Those (people) came from Ireland The first of the patterns was used with participles of transitive verbs. The verb habban preserved the meaning of possession. The above given phrase would mean: The king had his army divided into two parts. The second pattern took participles of intransitive verbs. The verb bēon and the participle in such sentences should be treated as a linkverb and a predicative. Towards the 12th century both patterns turned into analytical forms. That we ben entred in-to shippes bord That we have entered the ship He tellys that a scolere at Pares had done many full synnys He told that a pupil in Paris had done many sins форм. В результате к настоящему времени старые синтетические формы косвенных наклонений сохраняются лишь отчасти. Это формы, омонимичные инфинитиву без to ( I suggest that he do/be /take/etc.), и формы, омонимичные прошедшему времени изъявительного наклонения ( I wish he did/were /took/etc.). Первая из них развивалась из формы настоящего времени; вторая – из формы прошедшего времени сослагательного наклонения. OE (Сослагат. накл.) dō Наст.время, ед.ч. dōn Наст.время, мн.ч. dyde Пр.время, ед.ч. dyden Пр.время, мн.ч. > > > > do do did did NE (Сослагат. накл.) Сослагательное I Сослагательное I Сослагательное II Сослагательное II Как свидетельствует таблица, древнеанглийский субъенктив имел различия в числе, однако эти различия были нейтрализованы редукцией и последующей утратой безударных окончаний. 151. Залог (Развитие пассивных форм). Как упоминалось ранее (см. 075) значение пассивного действия передавалось в древнеанглийском языке с помощью двух синтаксических моделей: weorþan (become)+ Participle II и bēon (be)+ Participle II. Первая из них вышла из употребления еще в среднеанглийский период в связи с исчезновением глагола weorþan. Вторая модель постепенно преобразовалась в аналитическую форму be done. В среднеанглийский период и в последующие годы пассив приобрел перфектную и длительную формы и расширил сферу своего использования. 152. Категория временной соотнесенности (Развитие перфектных форм). Подобно другим аналитическим формам английского языка формы перфекта исходят из свободных синтаксических словосочетаний. В развитии перфекта принимали участие две синтаксические модели: habban (have) + Participle II и bēon (be)+ Participle II. Hæfde sē cyning his fierd on tū tonumen During the ME period both patterns were widely spread. However in the NE period the forms with be were ousted by the forms with have. Today the English language has but a few relics of the ME perfect with be: he is gone; he is arrived and the like. The Development of Non-Finite Forms 153. The Infinitive. With the reduction of unstressed endings in ME the two forms (Nominative and Dative) of the OE infinitive merged into one. N D OE wrītan to wrītane > > ME writen to writen The preposition to which was always used with the Dative form gradually lost its lexical meaning and turned into the formal sign of the Infinitive. In ME the infinitive developed its perfect form, and in NE it acquired the categories of aspect and voice. 154. The Participle. The OE verb built its first participle with the help of the suffix -ende, which was gradually ousted by the suffix -ing of the verbal noun (see 149). Towards the NE period the first participle acquired the forms of the perfect, continuous and passive. 155. The second participle developed in ME and NE towards modification of its sound and graphic form. The dental suffix used to build the second participle of weak verbs gradually developed its allomorphs [d], [t], [id] like in the verbs loved, worked, sounded. Participle II of some strong verbs lost the suffix -en. However many of the verbs retained this suffix. As a result in Modern English there are both participles with -en (written, driven, taken, spoken, etc.) and participles without it (dug, drunk, run, found, etc.). 156. Rise of the Gerund. The gerund appeared in the language as a The king divided his army into two (parts) Þa wæron cumene of Hibernia Those (people) came from Ireland Первая из этих моделей использовалась с причастиями переходных глаголов, причем глагол habban сохранял значение обладания: The king had his army divided into two parts. Во второй модели использовались причастия непереходных глаголов. Глагол bēon и причастие выступали в качестве связки и предикатива. К XII веку обе модели приобрели черты аналитических форм глагола. That we ben entred in-to shippes bord That we have entered the ship He tellys that a scolere at Pares had done many full synnys He told that a pupil in Paris had done many sins Обе формы широко использовались в течение среднеанглийского периода, однако в новоанглийский период формы с be были вытеснены формами с have. В современном английском языке сохраняются лишь отдельные устойчивые сочетания, представляющие собой остатки среднеанглийского перфекта с глаголом be: he is gone; he is arrived и т.п. Развитие неличных форм глагола 153. Инфинитив. С редукцией безударных окончаний в среднеанглийский период две падежные формы древнеанглийского инфинитива слились в одну. И Д OE wrītan to wrītane > > ME writen to writen Предлог to, который всегда использовался с формой result of mutual influence of the first participle and the verbal noun in –ing. The first participle borrowed from the verbal noun its suffix (e.g.: huntende > hunting, see 149), and the two forms became identical (hunting - gerund; hunting - participle). Such likeness had a reverse effect: the participle began to influence the development of the verbal noun. Under this influence the verbal noun gradually acquired some properties of a verb and turned into a new non-finite form: the gerund. In ME it began to take a direct object and adverbial modifiers. In NE the gerund developed the analytical forms of the perfect and passive. With acquiring more and more features of a verb the gerund lost its article. However many of its nominal properties were retained. Thus, the gerund preserved the syntactic functions of a noun and the ability to be used with prepositions and to be modified by a possessive pronoun. Changes in Morphological Types of the Verb 157. Weak Verbs. The development of weak verbs in ME and NE was marked by the following directions. 1. 2. Eliminating differences between the classes. Rise of new groups of irregular verbs. 158. It has already been mentioned (see 083) that classes of the weak verb in OE could be recognized by the type of endings. In accordance with the general tendency towards the reduction of unstressed vowels (see 104) all the endings came to nearly one and the same form in the ME period and the classes of the weak verb became indistinguishable. Cf.: Class I II Old English Infinitive Past temman (tame) temmede lufian (love) lufode Part. II temmed lufod дательного падежа инфинитива постепенно потерял свое лексическое значение и превратился в формальный показатель инфинитива. В среднеанглийский период инфинитив приобрел перфектную, а позднее длительную и пассивную формы. 154. Причастие. Первое причастие в древнеанглийском языке образовывалось при помощи суффикса -ende, который постепенно был вытеснен суффиксом отглагольного существительного -ing (см. 149). К началу новоанглийского периода причастие I стало употребляться в длительной форме, а также в формах перфекта и пассива. 155. В эволюции второго причастия (образованного от слабых глаголов) отмечается развитие алломорфов дентального суффикса, которые приняли форму [d], [t], [id]: loved, worked, sounded. Причастие II некоторых сильных глаголов потеряло суффикс -en. Однако многие глаголы сохранили этот суффикс. В результате система сильных глаголов современного английского языка имеет причастия как с -en (written, driven, taken, spoken, etc.), так и без него (dug, drunk, run, found, etc.). 156. Возникновение герундия. Появление герундия в английском языке является результатом взаимодействия первого причастия и отглагольного существительного на –ing. Первое причастие заимствовало этот суффикс у отглагольного существительного (e.g.: huntende > hunting, see 149). В результате в языке развивалась лексико-грамматическая омонимия (hunting герундий; hunting - причастие). В свою очередь, уподобившись в своей форме отглагольному существительному, причастие стало активно воздействовать на него. Под влиянием причастия отглагольное существительное стало приобретать глагольные черты: в среднеанглийский период эта форма стала использоваться с прямым дополнением и обстоятельствами; в новоанглийский период герундий приобрел аналитические формы перфекта и пассива. III libban (live) livde lived Middle English Infinitive Past Part. II temen temede temed loven lovede loved liven livde livd In NE the infinitive lost the ending -en, and the principal forms of weak verbs developed their modern shapes. Infinitive tame love liven New English Past tamed loved lived Part. II tamed loved lived 159. The phonetic phenomena which characterized the development of the language in ME and NE gave rise to some new irregular groups of verbs. A few verbs with the roots in -d, or -t developed into a group of verbs with no sound distinctions between the principal forms. OE ME NE settan setten set sette sette set sett set set Today this group is made up of such verbs as set (set, set), shut (shut, shut), cost (cost, cost), cast (cast, cast) and the former strong verb let (let; let). Some verbs with the root in -nd, -ld, -rd began to build their past and participle II with the help of unvoiced dental suffix -t. OE ME NE Modern sendan senden send verbs of this sende sened sente sent sent sent kind are send (sent, sent), learn (learnt, learnt), Превратившись в неличную форму глагола, герундий стал использоваться без артикля, однако он оставил за собой многие номинальные черты. В частности, герундий сохраняет синтаксические функции существительного, а также способности использоваться в предложных словосочетаниях и определяться притяжательным местоимением. Морфологические классы глагола Слабые глаголы. Развитие слабых глаголов в средний и новый периоды осуществлялось в следующих направлениях. 1. Исчезновение различий между классами слабого глагола. 2. Появление новых групп неправильных глаголов. 158. Как уже упоминалось (см.083), о принадлежности слабого глагола к одному из трех классов свидетельствовало его окончание. Однако в соответствии с общей тенденцией к усреднению безударных гласных (см. 104), все окончания в течение среднего периода были редуцированы до одной и той же формы. Таким образом, классы слабого глагола утратили свои различительные черты. Ср.: Class I II III Old English Infinitive Past Part. II temman (tame) temmede temmed lufian (love) lufode lufod libban (live) livde lived Middle English Infinitive Past Part. II temen temede temed loven lovede loved liven livde livd В новоанглийский период инфинитив утратил окончание -en, а глагольные формы развивались в соответствии со звуковыми и графическими явлениями данного периода. build (built, built), etc. Verbs which ended in -l, -m, -n, -v, also began to take the unvoiced suffix -t). These and a few other verbs developed a new sound interchange and formed a group of irregular verbs like feel (felt; felt), leave (left; left), keep (kept; kept). The new vowel interchange [i:], [e], [e] was caused by two phonetic phenomena: the shortening of vowels and the Great Vowel Shift. In ME the long vowel [e:] which was found in the root of these verbs was shortened before two consonants, that is in the past and the past participle (OE cēpte [e:] > ME kepte [e], see 105). In the infinitive the vowel remained long as it was followed by only one consonant (cēpan [e:] > keepen [e]). In NE the long vowel [e:] of the infinitive was narrowed in accordance with the Great Vowel Shift (ME keepen [e:] > NE keep [i:], see 108). The whole development of the new vowel interchange may be illustrated by the following chart. OE ME NE cēpan [e:] keepen [e:] keep [i:] cēpte [e:] kepte [e] kept [e] cēpt [e:] kept [e] kept [e] The new group of irregular verbs was replenished by some of the former strong verbs: sleep (slept; slept), read (read; read), weep (wept, wept). 160. Strong Verbs. The main changes in the system of strong verbs in ME and NE may be regarded under the following headings. 1. Reduction of principal forms from four to three. 2. Rearrangement of vowel gradation. 3. Transition of strong verbs into the class of weak verbs. 161. The number of principal forms was reduced from four to three because two of them (the past singular and the past plural) merged into one form. The past singular and the past plural of OE strong verbs could be Infinitive tame love liven New English Past tamed loved lived Part. II tamed loved lived 159. Фонетические явления, происходившие в языке в новый и средний периоды, привели к появлению новых групп неправильных глаголов. Так, глаголы с основами на -d, или -t развились в группу, в которой нет различий между главными формами глагола. OE ME NE settan setten set sette sette set sett set set Сегодня эта группа представлена такими глаголами, как: set (set, set), shut (shut, shut), cost (cost, cost), cast (cast, cast). К ним присоединился также один из бывших сильных глаголов, а именно глагол let (let; let). Глаголы с основами на -nd, -ld, -rd стали строить формы прошедшего времени и второго причастия с помощью глухого дентального суффикса -t. OE ME NE sendan senden send sende sente sent sened sent sent В современном английском в эту группу входят, например, глаголы send (sent, sent), learn (learnt, learnt), build (built, built), etc. Глаголы с основами на -l, -m, -n, -v, также стали принимать глухой дентальный суффикс -t. В этих и некоторых других глаголах развивалось чередование корневого гласного: feel (felt; felt), leave (left; left), keep (kept; kept). Чередование [i:], [e], [e] развивалось в результате двух distinguished by two markers. One of them was the ending -on found in the plural form (writon ). In accordance with the general tendency this ending was first reduced to -en and then towards the 16th century it was lost (on > en > e > lost). On the other hand the past singular and the past plural had different vowels of gradation in the stem (wrāt - writon), and with the loss of the ending -on the two forms of the past could still be distinguished (wrāt – writ). Two of the classes (VI and VII), however, had the same vowel for both numbers in the past (stōd – stōdon; cnēow – cnēowon). It is most likely that the verbs of these two classes started the process of neutralization of number distinctions in the past. When the ending -on was lost the singular and the past plural of these verbs merged into one form. In due time verbs of the other classes also began to use one and the same stem for both numbers. And the strong verb was left with only three principal forms. 162. Another important change that affected the strong verb in the course of its development was rearrangement of vowel gradation. It was caused by numerous phonetic phenomena that were taking place in the ME and the NE periods. Many of the verbs underwent individual changes. As a result verbs belonging to the same class could have different vowels in either of their forms. Class II Class IV Class V Class VI choose shoot bear steal give sit shake awake chose shot bore stole gave sat shook awoke chosen shot born stolen given sat shaken awoke Multiple phonetic changes undergone by strong verbs in ME and NE brought confusion to once strict and consistent rows of vowel фонетических явлений: среднеанглийского сокращения гласных и великого сдвига. В средний период долгий [e:] в корне этих глаголов сокращался перед двумя согласными, т.е. в формах прошедшего времени и второго причастия (OE cēpte[e:] > ME kepte [e], see 105). В инфинитиве же корневой гласный оставался долгим, так как за ним следовал лишь один согласный звук (cēpan [e:] > keepen [e]). В новый период долгий [e:] инфинитива сузился в соответствии с великим сдвигом гласных и перешел в [i:] (ME keepen [e:] > NE keep [i:], see 108). В обобщенном виде развитие нового чередования гласных можно проиллюстрировать следующей таблицей. OE ME NE cēpan [e:] keepen [e:] keep [i:] cēpte [e:] kepte [e] kept [e] cēpt [e:] kept [e] kept [e] Эта группа глаголов была далее пополнена некоторыми сильными глаголами, которые перешли в разряд слабых: sleep (slept; slept), read (read; read), weep (wept, wept). 160. Сильные глаголы. Система сильных глаголов английского языка претерпевала в средний и новый периоды следующие изменения. 1. Сокращение числа главных форм глагола. 2. Изменения чередования корневого гласного. 3. Переход некоторых сильных глаголов в разряд слабых. 161. Число главных форм сильного глагола сократилось с четырех до трех, поскольку две из этих форм (прошедшее время единственного и прошедшее время множественного числа) слились в одну. Различия между формами прошедшего времени единственного и множественного числа определялись в древнеанглийском языке двумя позициями. Одной из них было gradation. In addition strong verbs acquired some other asymmetric features. For example, some of the verbs lost the ending of the past participle -en (shot; found; sung; etc); the others retained it (chosen; given; written; shaken; etc). Some of the verbs developed different forms for the past and the past participle (sang - sung; ran - run; etc.); and with the other verbs these forms sound identically (found found; sat - sat; stood -stood). All this meant a step towards a decay of the system of strong verbs. 163. This decay was deepened by the transition of about 90 strong verbs into the class of weak ones. Among them are, for example: bake, bow, climb, grip, help, lock, starve, wash, walk. Note: It is interesting to note that indirect evidence of the decay of strong verbs may be found in methods of teaching English. Modern methods recommend to memorize the forms of the strong verbs rather than the system. It is easier to learn every individual form than to learn the modern system. 164. Preterite-Present Verbs. Only six preterite-present verbs survived through the ME and the NE periods (can; may; must; shall should; owe - ought; dare) . In the course of their development they modified their graphic and sound form and developed different shades of modal meanings. Note: The term modal verbs takes into consideration only semantic qualities of these verbs, though most of them have their own morphological features as well. Nearly all these verbs preserve their old morphological features. The present form of such verbs retains likeness to the past: it does not take -s to denote the third person singular. In the course of development they acquired more morphological features of their own: thus most of the modal verbs do not have the form of the infinitive. 165. The OE verb sculan split into two separate modal verbs: its present form gave rise to the verb shall (OE sceal > NE shall); its past form developed into should (OE scealde > NE should). The verb āgan also split into two verbs: owe and ought. The verb owe originated from the present stem (OE āg > NE owe). The verb ought developed from the past stem (OE ohte > NE ought). 166. Suppletive Verbs. Both of the OE suppletive verbs (beon и gān) are preserved in the language of today. The most remarkable changes окончание множественного числа –on (writon). Подчиняясь общей тенденции к редукции безударных гласных, это окончание сначала изменилось в –en, а к XVI веку было утрачено (on > en > e > ноль). Еще одной различительной чертой единственного и множественного числа прошедшего времени был корневой гласный (wrāt - writon), и с утратой окончания -on эти формы все еще отличались друг от друга (wrāt >wrōt – writ). Между тем сильные глаголы шестого и седьмого классов имели один и тот же гласный и для единственного, и для множественного числа (stōd – stōdon; cnēow – cnēowon). С редукцией и дальнейшей утратой окончания -on различия между формами единственного и множественного числа были нейтрализованы, а с течением времени это явление распространилось и на остальные классы сильного глагола. 162. Другим явлением, оказавшим важное влияние на развитие сильного глагола, стала реорганизация системы чередований корневого гласного. Ее истоками были многочисленные фонетические явления, происходившие в течение среднего и нового периодов. При этом многие глаголы, претерпевали изменения индивидуального характера. В результате некоторые классы сильного глагола стали характеризоваться сразу несколькими рядами чередования корневого гласного. Класс II Класс IV Класс V Класс VI choose shoot bear steal give sit shake awake chose shot bore stole gave sat shook awoke chosen shot born stolen given sat shaken awoke Иными словами, некогда стройная система аблаута стала приобретать хаотичные черты. К тому же эта хаотичность усиливалась ассиметрией в системе сильного глагола. Например, undergone by these verbs were the following. In ME the verb been (NE be) lost the parallel forms, but acquired the past participle been (NE been) which was missing in the paradigm of the OE verb. As its plural this verb began to use the form aren (NE are) borrowed from the Northern dialects. The verb goon (NE go) acquired a new form of the past - went. This form was borrowed from the verb wenden (to turn). The OE past forms (ēode, ēodon) fell in disuse. 167. To sum up the survey of the morphological changes within the verb system one can conclude it with the following. 1. Weak verbs proved to be by far the most influential group. In the course of the evolution these verbs consolidated their position in the language. They retained the pattern of building the main forms and made this pattern the only productive one in the language. 2. The system of strong verbs approached its decay. The vowel gradation was retained, but it lost the outward signs of its systematic arrangement. Besides strong verbs were greatly decreased in number. 3. Preterite-present verbs partially lost and partially retained their morphological distinctions. Having developed new morphological and semantic features they practically formed a new group of verbs (modal verbs). 4. Suppletive verbs retained their main morphological features, and remained the smallest group of verbs. 168. All these changes practically meant rearrangement of the verb system, and this rearrangement is reflected in the modern morphological classification. The classification divides all the verbs into two groups: standard (regular) verbs and non-standard (irregular) verbs. The first is a large group of verbs which build their principal forms with the help of the dental suffix -ed. The second is a group of verbs employing other means to build their past and participle II. The first group is made up of former weak verbs (work; love; live; etc) окончание второго причастия -en было утрачено одними глаголами (shot; found; sung; etc), однако сохранилось в других (chosen; given; written; shaken; etc). Одни глаголы сохранили различия в формах прошедшего времени и второго причастия (sang - sung; ran - run; etc.); у других эти формы стали омонимичными (found - found; sat sat; stood -stood). Все это означало распад системы сильного глагола. 163. Этот распад усилился с переходом около девяноста сильных глаголов в систему слабых. К таким глаголам относятся, например, bake, bow, climb, grip, help, lock, starve, wash, walk. Примечание: Интересно что, распад системы сильного глагола косвенно подтверждается методикой обучения английскому языку, которая рекомендует запоминать не систему, а каждую индивидуальную форму. Сегодня проще выучить каждую форму, чем разобраться в современной системе. 164. Претерите-презентные глаголы. Из двенадцати претерите-презентных глаголов древнеанглийского языка к настоящему времени сохранились лишь шесть (can; may; must; shall - should; owe - ought; dare). В ходе своего развития каждый из них модифицировал свою графическую и звуковую форму и приобрел различные оттенки модальных значений. Примечание: Термин модальный принимает во внимание лишь семантические черты данных глаголов хотя большинство из них сохраняют и старые морфологические свойства. Форма настоящего времени этих глаголов сохраняет сходство с прошедшим в том смысле, что эта форма не принимает окончания -s для обозначения третьего лица. В ходе эволюции эти глаголы приобрели и новые морфологические черты, свойственные лишь данной группе глаголов: большинство из них не имеют формы инфинитива. 165. Древнеанглийский глагол sculan стал источником двух современных модальных глаголов: форма настоящего времени эволюционировала до состояния shall (OE sceal > NE shall); форма прошедшего времени развилась в модальный глагол should (OE scealde > NE should). Аналогичным образом эволюционировал и глагол āgan, который стал источником глаголов: owe и ought. Owe исходит из формы настоящего времени (OE āg > NE owe); ought – из формы and some of the former strong verbs which began to build their main forms by means of the dental suffix -ed (bake; bow; climb; grip; help; starve; etc). The group of irregular verbs is rather heterogeneous from the view point of etymology. It includes: a) b) c) d) a set of former strong verbs (write; chose; find; steal; etc); the former preterite-present verbs (can; may; ought; etc); the suppletive verbs (go; be); a set of former weak verbs that developed irregular features at this or that period of their evolution (bring; tell; keep; send; cost, etc, see 084, 159). прошедшего времени (OE ohte > NE ought). 166. Супплетивные глаголы. Древние супплетивные глаголы (beon и gān) прошли путь эволюции английского языка, претерпев при этом ряд существенных изменений. В течение среднего периода глагол been (NE be) потерял свои параллельные формы и приобрел форму причастия прошедшего времени been (NE been), которая отсутствовала в парадигме древнего глагола. В качестве формы множественного числа этот глагол стал использовать форму aren (NE are), затмствованную из северных диалектов. Глагол goon (NE go) приобрел новую форму прошедшего времени went. Эта форма была заимствована у глагола wenden (to turn). Старые формы прошедшего времени (ēode, ēodon) вышли из употребления. 167. В завершение обзора морфологических изменений в системе английского глагола можно привести следующие обобщения. 1. Слабые глаголы упрочили свои позиции в языке. Они сохранили модель построения главных форм, которая осталась единственной продуктивной моделью в системе английского глагола. 2. Система сильных глаголов пришла в состояние распада. Сильные глаголы сохранили чередования корневого гласного, однако эти чередования утратили признаки систематической организации. К тому же группа сильных глаголов значительно сократилась в числе. 3. Претерите-презентные глаголы сохранили свои морфологические черты лишь отчасти. В ходе своего развития они приобретали новые морфологические и семантические свойства, которые выделили их из прочих глаголов в отдельный класс – класс модальных глаголов. 4. Суплетивные глаголы остались самой малочисленной группой, сохранив при этом свою главную отличительную особенность – использование нескольких корней для образования своих форм. 168. Все эти изменения привели к реорганизации морфологических классов английского глагола. Современная классификация разделяет английские глаголы на два класса: класс стандартных (правильных) глаголов и класс нестандартных (неправильных) глаголов. Первый из них составлен большой группой глаголов, образующих свои главные формы при помощи дентального суффикса -ed. Второй класс составлен из глаголов, для построения главных форм которых задействуются иные средства. В класс стандартных глаголов входят бывшие слабые глаголы (work; love; live; etc) и несколько из старых сильных глаголов, заимствовавших модель построения прошедшего времени и второго причастия у слабых глаголов (bake; bow; climb; grip; help; starve; etc). Класс нестандартных глаголов неоднороден с точки зрения этимологии его составляющих. В этот класс входят: a) группа бывших сильных глаголов (write; chose; find; steal; etc); b) бывшие претерите-презентные глаголы (can; may; ought; etc); c) супплетивные глаголы (go; be); d) группа слабых глаголов, у которых развивались нестандартные черты в различные периоды эволюции английского языка (bring; tell; keep; send; cost, etc, см. 084, 159).