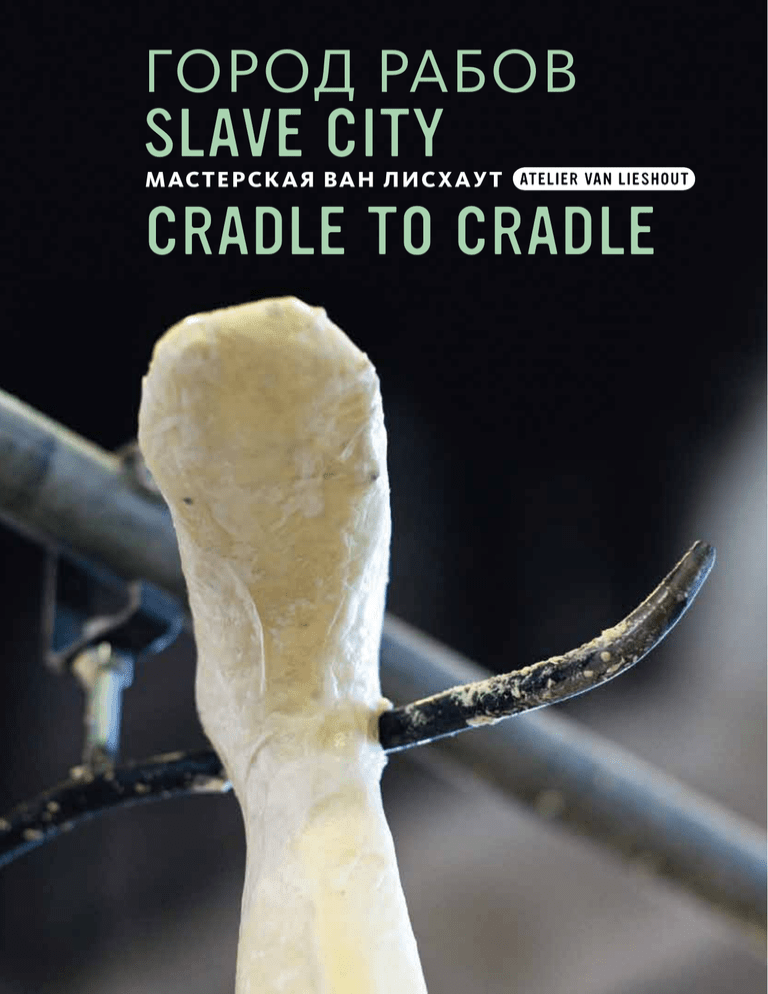

Мастерская ван Лисхаут

advertisement